They can load a million containers a year, but they are now operating at half capacity as Europe's economic meltdown erodes demand for items such as electronics, dragging a struggling global shipping industry deeper into the abyss.

"People buy less of the unnecessary stuff; they are now satisfied with one television set instead of three, and that is typically all the things imported from China that are being reduced," says Johan Uggla, the terminal's managing director and a grandson of 98-year-old shipping magnate Maersk Mc-Kinney Moller.

Shipping firms, banking on rapid trade growth, went on a binge, ordering new vessels in 2007 and 2008, many of which are being delivered this year. They face severe overcapacity just as demand, particularly on the once lucrative routes between Europe and Asia, falls through the floor.

So what is in store for 2012?

"In one word: bloodletting," says private equity investor Andreas Beroutsos, a founder of One Point Capital Management.

"Some bankruptcies, shrinking, consolidation, very limited new orders, cancellation of large parts of the order book and cyclically elevated scrapping," he added.

Soaring fuel costs, Europe's crisis and the lack of bank financing are likely to worsen a four-year-long shipping crisis and extend it well into 2013.

Container and bulk shipping companies, which transport everything from grain to coal to consumer goods, have already burned through much of their cash.

PT Berlian Laju Tanker , Indonesia's largest oil and gas shipping group, this week defaulted on its $2 billion debt, while the auditors of Danish bulk and tanker firm Torm A/S expressed doubts on Thursday about its ability to remain a going concern through 2012.

Even the biggest are not immune.

Norway's Frontline recently gave up its status as the world's largest tanker firm as the crisis forced it to shed 20 percent of its fleet and most of its orders for new vessels.

Denmark's A.P. Moller-Maersk, the world's biggest container liner, predicted another loss-making year for the segment after closing 2011 in the red.

Looking to China

The U.S. recovery, while welcome, does little to help, because container firms rely heavily on Asia-Europe trade and tanker firms rely on trade into Europe, operators said.

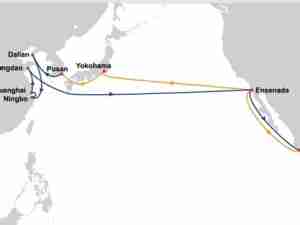

The Aarhus cranes, which can lift containers as high as 60 meters, this week serviced the 400-metre Eugen Maersk - unloading Asian-made consumer goods and loading Danish farm products for a trip to China through the Suez Canal.

"It's a great benefit to Denmark to have a ship calling directly from the Far East," said Peter Hag, head of operations at the container terminal, standing on the red-painted deck of the Eugen Maersk with 10 layers of containers stacked below deck and seven to nine layers above deck.

"This is the new market - China," said Hag. "Even if we sell all the pork we have in Denmark, we'll still be feeding only a small percentage of the Chinese."

But European container imports from Asia fell by over 9 percent in the fourth quarter, and box rates plunged 25 percent over the year as the euro zone heads for an almost certain recession.

"We are a good example of what Europe is experiencing," Uggla said at his office overlooking the quay. "We survived (2011). We are profitable but not what our shareholders expect."

Meanwhile, soaring bunker prices, which account for up to 70 percent of shipping costs, are making smaller vessels obsolete, often well before their normal lifespan.

Japan's Mitsui O.S.K. Lines recently decided to scrap five tankers, with the youngest of them built in 1998, an unusually young vessel on the scrap yard.

Living Dead

The only good news for bulk and container firms is that banks are desperately trying to avoid seizing assets.

"Companies should go bankrupt, but they won't. They'll be the living dead, who pay no dividend and just vegetate," said Erik Nikolai S