NE PORTS / CHEMICALS 2008 - Post-9/11 mandates impact transportation of chemicals

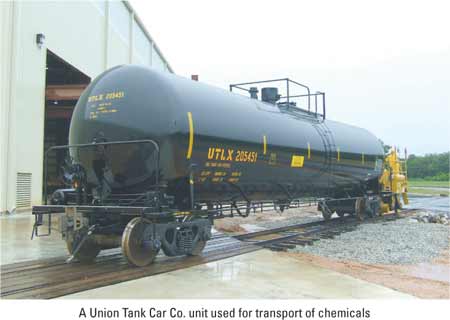

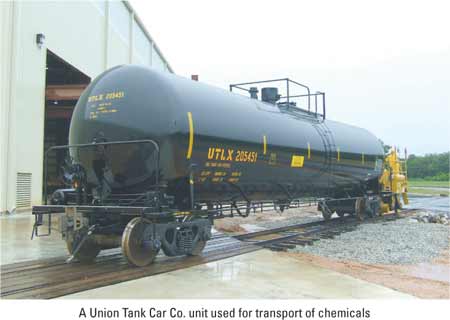

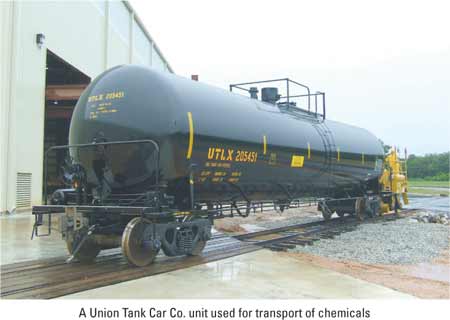

By Paul Scott Abbott, AJOTPrivate and public sectors are working together to enhance security and safety of transportation of chemicals, both through new procedures and the development of next-generation rail tank cars.

The multibillion-dollar process is being propelled by mandates enacted following the tragic events of Sept. 11, 2001, and is further evolving this year as existing mandates are being fulfilled and Congress considers additional legislation.

Key elements include rail routings that limit the transit of chemical-carrying rail cars through high-threat areas, reductions in the amount of time such tank cars are at rest and protocols for the “positive handoff” of these rail cars when they enter and leave chemical facilities.