As Trump Keeps U.S. From Iran, Russia and China Step In

By: | Aug 06 2017 at 03:00 AM

Decades-old sanctions preventing U.S. oil companies from having any dealings with Iran, combined with President Donald Trump’s antipathy towards his predecessor’s nuclear deal, have created a fertile environment for America’s rivals in the Persian Gulf country. As Iran takes advantage of its new economic freedom, American oil companies will likely see all their opportunities snapped up by Chinese, Russian and European firms—just as they did less than a decade ago in Iraq.

U.S. companies have been banned from investing in Iran, or buying Iranian oil, for close to 40 years. That did not change with the 2015 agreement —the snappily titled Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action—and leaves American oil firms as the biggest losers from the arrangement. That’s not to say that there were no beneficiaries. One exception to the ban is makers of commercial aircraft and parts, and Boeing Co. already has orders for as many as 120 planes from two Iranian carriers, although these are still under review by the U.S. Treasury Department.

But if the U.S. oil sector will see no benefit from the easing of international sanctions on Tehran, the same cannot be said for companies elsewhere. Back in January Iran published a list of 29 companies pre-qualified to bid for oil and gas projects in the country, adding five more in June. The list includes Royal Dutch Shell Plc, Italy’s ENI SpA, Rosneft PJSC and Gazprom PJSC from Russia, as well as Sinopec and CNOOC Ltd. from China. BP Plc, whose corporate roots begin in Persia, elected not to seek pre-qualification—the U.S. citizenship of its Chief Executive Officer and many senior managers complicated the process for the company.

This is only a small first step, though. President Trump’s vocal opposition to the nuclear deal has created uncertainty around its sustainability that is undoubtedly slowing the pace of investment. In an echo of the difficulties that surrounded the resumption of Iranian oil exports to Europe early last year, it is the supporting cast that is most hesitant.

Back then it was insurers who were reluctant to provide cover for Iranian cargoes and the vessels booked to carry them to European ports. Banks’ concerns about the snapback of sanctions may prove to be the biggest stumbling block for projects now being considered. They will have to underwrite the billions of dollars needed to rehabilitate Iran’s aging oil fields and develop its more recent discoveries.

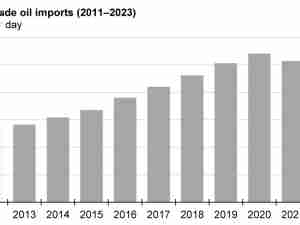

Just as the ramp up in Iranian oil exports first favored Asia, with shipments to China and India increasing before flows to European Union countries resumed, the re-opening of its upstream oil and gas sector may well do the same.

There has been a slow trickle of oil and gas project partnerships announced by Tehran. Undoubtedly the biggest so far is the development by France’s Total SA and China National Petroleum Corp. of Phase 11 of the South Pars gas field, which is the world’s largest, and straddles the border between Iran and Qatar (where it is known as the North field). Preliminary deals for smaller oil and gas deposits have been signed with Russian and Japanese companies. And Chinese and Russian firms have expressed interest in developing some of the largest deposits on offer in the country. Don’t expect the leaders of any of these countries to stand in their way.

The outcome of the rush of activity in Iraq around 2010 is a good guide to where this is headed. There, Exxon Mobil Corp. is the only U.S. representative among a host of European, Russian and Asian firms.

President Trump may wish to end the nuclear pact with Iran and stop investment plans in their tracks. He certainly came close to killing the deal last month. But he will struggle to rebuild the international coalition put together by President Barack Obama that successfully pressured Iran into accepting limits on its nuclear ambitions.

While European countries may find themselves reluctantly dragged along with any U.S. move to scrap the deal, don’t expect any support from Russia or China. The president has done little to endear himself to the leadership in Moscow or Beijing since assuming office.

The longevity of the Castro brothers in Cuba, a succession of Kims in North Korea and the Islamic Republic in Iran itself attest to the weakness of broad-based sanctions as a tool to bring about change. Decades of enforced isolation may have reduced their populations to varying degrees of desperation, but did little to unseat the leaders at whom the sanctions were aimed.

If the U.S. wishes to keep its companies out of Iran that is, of course, its right. It just might find it difficult to carry the rest of the world with it this time around.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of Bloomberg LP and its owners.

_A_-_28de80_-_38f408a0a1c601cdbf9fe70c9d30a28084a5da3d_lqip.jpg)