Flood of U.S. Oil to Asia Comforts Tanker Market Trashed by OPEC

By: Alex Longley | Apr 06 2017 at 06:15 AM | Maritime

OPEC all but trashed the tanker market with its output cuts. That the damage hasn’t been even worse is thanks in large part to a flood of U.S. crude exports, particularly to Asia.

China zoomed past Canada to become the biggest foreign destination for American crude in February, accounting for more than 8 million barrels of U.S. cargoes. Tanker tracking is indicating no let up in U.S. oil flooding to Asia in March, boosting shipments on what is one of the industry’s longest-distance trade routes.

Freight rates for oil collapsed this year after the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries and other nations reliant on crude sales announced production cuts in a bid to prop up prices. The curbs have driven Chinese and other Asian buyers to places like the U.S. and the North Sea to source crude like never before, adding the vital ingredient of distance to tanker demand.

“The U.S. exports have been a big saving grace,” said Jonathan Lee, chief executive officer of Tankers International LLC in London, operator of the world’s biggest pool of supertankers, known in the industry as very large crude carriers. “Is America becoming a swing producer of pricing and quantities? For us there could be an argument to say yes.”

Crude tankers heading to Asia

The U.S. exported 8.08 million barrels of U.S. light crude to China in February, nearly quadrupling its January flows, according to data released by the U.S. Census Bureau Tuesday. That helped boost total monthly U.S. exports to a record 31.2 million barrels.

Tanker tracking data show a continuation of the trend. Supertankers with the capacity to move 4 million barrels are en route to Chinese ports. A further 7 million barrels are being shipped to Singapore, a refueling point for vessels ultimately sailing to China. All the ships in question are sailing east, rather than around South America and across the Pacific Ocean. The data include deliveries on 1 million-barrel hauling vessels called Suezmaxes, which Lee says are also benefiting from the surging U.S. outflow.

Even so, the shipments from the U.S. and elsewhere in the Atlantic Basin only mean rates are less bad than would they would have been otherwise. OPEC, along with its non-member allies, pledged to cut about 330 million barrels from the global oil market in the first six months of this year. With about 40 percent of global crude output getting moved by sea, that would imply the removal of about 130 million barrels from the supertanker market. There’s also speculation that the cuts, initially planned to run for six months from January, may be extended through December.

“If you look at total crude exports, it’s down,” said Frode Moerkedal, an analyst at Clarksons Platou Securities, the investment banking unit of the world’s largest ship broker. “Overall the slowdown in volume growth has trumped the increase in trading distances.”

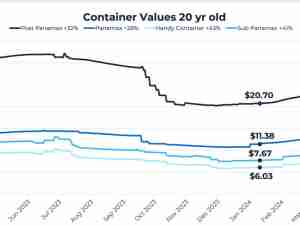

Even so, while benchmark tanker rates fell from around $70,000 a day in December to below $15,000 a day in March, they still cover basic costs. In the worst markets, owners are sometimes willing to contribute to fuel costs on certain trade routes. Expenses like crew, insurance and repairs amounted to $10,159 a day for an average VLCC in 2015, according to the most recent estimate from Moore Stephens, a consulting firm in industry expenses.

That rates aren’t worse is partly thanks to Asian refiners scouring the earth to replace supplies lost from OPEC’s core members in the Middle East. West African exporters—including Nigeria, which is exempt from the producer club’s cuts—are sending record amounts of oil to Asia this month, tanker tracking data show.

Those surging supplies from the Atlantic Basin have helped prevent earnings from falling much below a ship’s operating costs, said Andreas Wikborg, equity analyst at Arctic Securities. Central and South American producers have been adding support too, boosting output and sending more to Asia, he said. At the same time, the North Sea sent an additional nine million barrels of crude to Asia in the first three months of 2017 compared with 2016.

“Definitely the Atlantic Basin is helping keep rates at an ‘OK’ level compared to where they could have been,” Wikborg said. “An OPEC cut is bad news for tankers, but part of the lost volumes are to a degree being compensated for by increased distances. If the U.S. export ban hadn’t been lifted it would have put increased pressure on rates.”