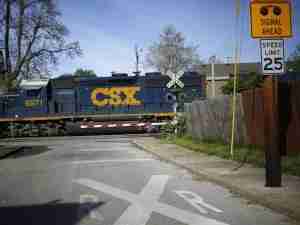

North American railways have traditionally taken a back seat to pipelines when it comes to shipping crude oil, but Green and other rail executives say the prolific Bakken deposit is a chance to change that dynamic.

The Bakken field, which the U.S. Geological Survey estimates could hold as much as 4.3 billion barrels of oil, has emerged recently as one of North America's hottest energy plays.

New technologies are allowing producers to tap the reserves that lie mostly under the Canadian province of Saskatchewan, and North Dakota and Montana in the United States.

Canadian Pacific and Canadian National Railway have tracks in the region and see an opportunity to snag a piece of crude oil shipping for the long run before the pipeline infrastructure is built up.

CP's shipments of oil from North Dakota on its Soo Line mainline from Canada to Chicago jumped in the past year to about 8,000 cars a year, up from 500, and it sees that growing to between 30,000 and 35,000 cars per year.

Green believe that growth can spread north as the Canadian portion of the Bakken field is developed.

"Our line runs right through the Saskatchewan Bakken, and we are already in dialogue with parties to see if we can replicate what we are doing in North Dakota in Saskatchewan," he told analysts recently.

Playing the Flexibility Card

Although more expensive than using pipelines, shipping by rail is more flexible, allowing producers to route shipments to refineries that are paying more for crude and avoid the brimming Cushing, Oklahoma, oil pricing hub.

That arbitrage advantage will allow the railroads to maintain more of a market share than they traditionally would have once the pipeline infrastructure in the region is built up, according to Green.

"It looks like the lifecycle here is not short, but rather long, and could be a sustained business for a decade or longer."

Green's view is endorsed by Roger Gadd, general manager of Saskatchewan's Great Western Railway, a 400-mile grain-hauling carrier that has found itself in the heart of the oil field and is also talking to potential customers.

"I think it is a long-term thing," said Gadd, noting that the only major pipeline through the region is already running at capacity and the alternative of moving crude long distances by truck is simply too expensive for drillers.

Canadian National's lines do not extend into North Dakota, but the carrier is enjoying increased oil traffic on its southern Saskatchewan branch lines, as well from shipping in sand needed for the multistage fracking method used to tap the field, along with other supplies needed in by drillers.

CN has moved 1,900 cars of Bakken-related freight since October, including 600 with oil, a spokesman said.

Transportation analysts say the railways are largely benefiting now from a lack of pipeline capacity, but the argument they will be able market their greater flexibility in the future does have merit despite their higher rates.

For instance, Canadian National said some of its shipments have gone toward northern Alberta rather than south to U.S. refiners because Bakken crude is being used as a diluent for the heavy bitumen wrung from the oil sands.

A spokesman for the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers stressed that the amount of oil moving by rail is still very small, but the industry welcomes having the extra option available.

The oil traffic will also require new capital spending by railways as Prairie lines geared to seasonal grain hauling are upgraded. CP was already adding capacity to its mainline and CN said it will do it as business warrants. (Reuters)