Threat of Venezuelan Oil Ban Pits Oil Boss Hamm Against Refiners

By: Jennifer A. Dlouhy, Bill Allison and Meenal Vamburkar | Aug 11 2017 at 04:00 AM | International Trade

The prospect of a U.S. blockade of crude oil imports from Venezuela has ignited fierce lobbying in Washington pitting domestic energy producers such as oil tycoon Harold Hamm, who favor a get-tough approach, against refiners that depend on those supplies.

Hamm said hitting Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro where it counts would deter the socialist leader’s moves to undermine democracy and consolidate power. In an interview, the Continental Resources, Inc. chief executive officer urged President Donald Trump to block the oil, a vital source of revenue for Venezuela.

“If the president wants to make an immediate impact on Venezuela to stop these human rights abuses and restore the situation, he’s got the ability to,” said Hamm, speaking as head of the Domestic Energy Producers Alliance, whose members include producers, oilfield service companies and independent oil and gas associations.

Opposing the ban are refiners such as Chevron Corp., Phillips 66, and Valero Energy Corp., which have warned that choking off shipments of Venezuelan crude would starve refineries designed to process the country’s heavy oil, leaving them searching for alternative supplies and driving up gasoline prices.

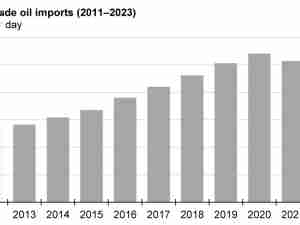

The stakes are high for both countries. Venezuela is the third-biggest supplier of oil imports to the U.S.—more than 270 million barrels worth about $10 billion last year—and that trade is a major source of revenue for the South American country.

Hamm was a vocal supporter of Trump’s presidential bid, eventually agreeing to advise him on energy policy. Trump, in turn, repeatedly lavished praise on Hamm, during campaign stops in front of industry-heavy audiences in North Dakota and Pennsylvania.

When it is unified, the oil industry is a lobbying powerhouse in Washington, leaning on allies in the top ranks of the Trump administration as well as on Capitol Hill to advance its policy priorities. Oil and gas interests rank fourth among industry lobbying, with $64 million spent through the first six months of 2017, according to the not-for-profit Center for Responsive Politics, which analyzes lobbying and campaign finance data.

Refiners have been pressing their case with the Trump administration since June, as the White House considers ways to pressure Maduro and discourage a rewrite of Venezuela’s constitution. On Wednesday, the Trump administration froze the assets of eight Venezuelans, building on previous sanctions against 13 people associated with the Maduro regime.

White House officials have prepared a menu of possible additional sanctions against Venezuela but are divided over whether—and when—to take actions that could exacerbate the country’s deteriorating humanitarian and economic situation. The progressive approach envisioned by administration officials includes blocking exports of U.S. oil to Venezuela followed by limits on oilfield service firms doing business in the country and, finally, restricting imports of Venezuelan crude to the U.S. Those restrictions could be phased in gradually.

The prospect has inspired frantic appeals by companies that spent billions optimizing at least 20 different refineries to process heavy crude from the country. The leading refining trade group, the American Fuel and Petrochemical Manufacturers, sent two letters to Trump last month warning that a blockade would destabilize crude markets, causing an increase in oil prices as refiners scramble to replace Venezuelan supplies with ill-fitting, higher-cost substitutes and leading to bigger gasoline bills for consumers.

Sanctions may not even work as intended, as Venezuela finds other outlets for its crude beyond the U.S., said AFPM President Chet Thompson.

“We think that the United States could take this action, and it won’t have the desired effect, but it will have the unintended consequences of hurting consumers and refiners,” Thompson said in an interview. “This is more than just a passing concern.”

“Folks have spent many billions of dollars over the last several years to really optimize around Venezuelan crude, so any disruption of it could be a really big deal,” Thompson said.

Besides Venezuelan-owned Citgo Petroleum Corp., the refiners most dependent on Venezuelan crude are Valero, Phillips 66, Chevron and PBF Energy Inc. They are also the most active in lobbying against a crude import ban, according to accounts by four people familiar with the activity.

Last year, Valero took in roughly 54 million barrels from Venezuela while Phillips 66 and Chevron imported 46 million barrels and 33 million barrels, respectively. And while companies are already working to pare their dependence on Venezuelan crude, that is a heavier lift at some refineries. For instance, Venezuelan oil accounted for 43 percent of Chevron’s Pascagoula refinery’s capacity last month, according to U.S. Customs data compiled by Bloomberg. It represented 62 percent at Valero’s St. Charles facility.

Refiners have made direct appeals to administration officials and are courting Gulf Coast lawmakers, asking them to amplify their concerns with the White House. Those efforts paid off Thursday when the U.S. senators from Texas and Louisiana sent a letter to Trump arguing crude sanctions would be self defeating.

Sanctions targeting the oil sector would increase the likelihood of a disorderly default, hastening Russian consolidation of Venezuelan and Citgo oil assets, while diverting Venezuelan crude to China, harming the global competitiveness of U.S. businesses and raising costs for consumers, they said.

Asked about Chevron’s lobbying on the issue, a spokesman said the company “engages with the administration and Congress to provide our perspectives on complex energy issues to help shape an effective and responsible U.S. energy policy.”

Phillips 66 declined to comment. Representatives of PBF and Valero didn’t respond to requests for comment.

Oilfield service providers also have been discouraging the Trump administration from imposing sanctions that limit their business in the country, including contracts with the state-owned oil company Petróleos de Venezuela SA, or PDVSA. That option had been presented by some refiners as an alternative to throttling down Venezuelan crude imports.

Excluding U.S. companies from working in Venezuela doesn’t help further democracy there, the oilfield service firms argue; instead, it blocks their ability to recoup debt and gives competitors a chance to gain a foothold in the market.

The world’s four biggest oil service providers—Schlumberger Ltd.; GE’s Baker Hughes; Halliburton Co., and Weatherford International Plc—have kept a presence in Venezuela in order to work for some large, integrated oil companies, James West, an analyst at Evercore-ISI, wrote Thursday in an email. None of the companies give specifics for how many wells they are drilling or the size of their crews there.

Hamm is advocating that the Trump administration also cut off Venezuela’s access to light sweet, U.S. oil—like the kind flowing from Texas and North Dakota, where his Continental Resources is pulling crude from the Bakken formation. Venezuela blends U.S. light oil with its heavy crude before shipping the mixture to foreign refiners.

Hamm said his recommendation has been conveyed to the White House, though he did not elaborate on how.

Oil companies are still reeling from their last lobbying fight—a battle to weaken possible sanctions in legislation targeting Russia. The industry scored a partial win, when lawmakers agreed to set a threshold for Russian involvement high enough to remove the threat to some U.S. oil company projects around the world.

The threat of more sector-based regional sanctions is a disturbing trend, lobbyists said.

Citgo has made overtures to the Trump administration. It contributed $500,000 in December to the incoming president’s inaugural committee, according to Federal Election Commission records. The company didn’t contribute to inaugurations in 2005, 2009 or 2013.

Citgo has hired three lobbying shops, including Avenue Strategies, the firm co-founded by former Trump campaign manager Corey Lewandowski, paying it $80,000 from April to June. Lewandowski, who was not a registered lobbyist for Citgo, left Avenue Strategies in May. Two other veterans of the Trump campaign, senior adviser Barry Bennett and Arkansas state chairman Bud Cummins, represent the company.

They list the potential impact of “energy and foreign policy restrictions” on its client as a specific issue, and are lobbying the Treasury Department and the White House. Neither Bennett nor Cummins returned phone calls seeking comment.