U.S. Gas Exporters Brushing Aside Qatar’s Grab for Market Share

By: Naureen S. Malik | Jul 06 2017 at 12:01 AM

America’s gas exporters are, at least for now, brushing aside Qatar’s bid to claim a bigger share of the global market.

Qatar’s plan to dramatically boost gas output signaled to rivals including Australia and the U.S. that the race is on to find buyers and lock them into long-term contracts. American LNG exporters have already spent years pursuing such agreements, with President Donald Trump promoting their product in recent meetings with Chinese and Japanese leaders. Last week, South Korea said it would consider buying into three U.S. LNG projects.

The reaction from Meg Gentle, chief executive officer of U.S. LNG exporter Tellurian Inc., to Qatar’s ramp-up: The world needs more LNG capacity to meet growing demand, and “we welcome all potential supply sources.” Zdenek Gerych, a spokesman for U.S. LNG terminal developer Freeport LNG, said Wednesday, “My only comment on the Qatar issue: ‘They have to sell the volumes first.”’

Indeed, the impact of Qatar’s gas plans—announced just as Arab nations that severed ties with the country gathered in Egypt to discuss a path forward—will hinge largely on whether the world’s biggest liquefied natural gas supplier can secure even more long-term supply agreements with buyers in Europe and Asia. These contracts, typically lasting 15 to 20 years, have been crucial to keeping LNG projects around the globe moving forward. Without them, proposals have fallen apart amid a worldwide supply glut.

“Qatar will need to find off-take agreements to increase their supply that significantly,” said Charlie Riedl, executive director of the Center for Liquefied Natural Gas, a Washington-based industry group. U.S. projects, meanwhile, remain “well-positioned to respond to increasing demand” for LNG going into the next decade, he said.

U.S. exporters already have contracts to supply more than 80 million metric tons of LNG a year, according to estimates compiled by Bloomberg New Energy Finance. Developers are vying for more in an effort to secure financing to build terminals over the next decade.

Since the first cargo of shale gas set sail last year, America’s gas has reached about two dozen countries, reshaping how LNG is traded and setting the U.S. on a course to becoming a net-exporter of the fuel for the first time in decades. Some industry executives including Enbridge Inc. Chief Executive Officer Albert Monaco have suggested the U.S. may even jump ahead of Qatar and Australia to become the world’s biggest LNG supplier by 2035—a threat Qatar may be looking to quash with its latest move.

Qatar Petroleum plans to boost gas output by 30 percent to 100 million tons a year within seven years through a new project in the country’s North Field, the state-owned producer said Tuesday. Prior to this announcement, analysts including Energy Aspects Ltd. forecast that the country would lose its title as the world’s biggest LNG supplier to Australia.

Qatar still stands to make life more difficult for U.S. LNG suppliers. The North Field will allow the country to sell more of some of the cheapest gas in the world, Victoria Zaretskaya, a Washington-based analyst for the U.S. Energy Information Administration, said by email. That’ll have “major implications” for LNG export terminals that companies are proposing to build in the U.S. in the next decade, she said.

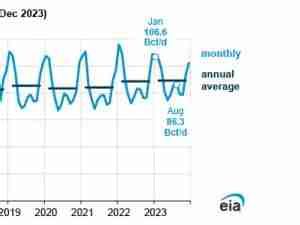

Boosting output in Qatar may end up jeopardizing one the country’s own projects. Zaretskaya said more supplies from the North Field could put the Golden Pass LNG terminal in Texas, being developed by a joint venture between Qatar Petroleum, Exxon Mobil Corp. and ConocoPhillips, at risk. Other projects that may be affected are Liquefied Natural Gas Ltd.’s Magnolia LNG terminal and the Lake Charles project being proposed by Energy Transfer and Royal Dutch Shell Plc, both in Louisiana, she said. Altogether, they’ve gained approval to liquefy 5.2 billion cubic feet of U.S. gas a day.

These projects “won’t go forward without a clear understanding” of which customers and what markets will take their supplies, Zaretskaya said.

“We are entering an interesting period of ‘courtships’ between prospective sellers and buyers,” she said. “And there may be some other factors to play in who gets the contracts and what other concessions were made to ‘sweeten the deal.”’