Vessel size, alliances raising pressure on some U.S. ports

posted by AJOT | Aug 10 2015 at 11:34 AM | Ports & Terminals | Liner Shipping

The rise of alliances among shipping carriers and industry moves towards post-Panamax and ultra large cargo ships are pressuring many U.S. ports to address access restrictions. The widening of the Panama Canal, slated to open in 2016, will further intensify the need to accommodate larger ships. Some regional ports that serve secondary markets and are unable to process larger vessels risk losing some services or being skipped completely, Fitch Ratings says.

The combined impact of the shift to larger vessels and carrier alliances is giving shippers significant negotiating leverage over ports. Carriers are seeking economies of scale through higher utilization of each vessel, which can result in fewer vessel calls overall. Furthermore, larger vessels can limit an individual carrier's reliance on any particular port or terminal. This has led to a reduction in the number of ports called on each voyage, raising pressure on ports to improve terminal capability and productivity.

Some ports which already have adequate water depth are investing to improve the efficiency of existing terminal facilities, seeking to maintain or improve their positions by increasing their share of first call services. Trends towards consolidating services could leave smaller regional ports at risk of losing some services or skipped completely by carriers.

Recent challenges seen at the Port of Portland are an example of how quickly the pressure on ports has risen. A project to deepen the 110-mile Columbia River deep-draft navigation channel from 40 feet to 43 feet was completed in 2010, but was insufficient to accommodate larger ships needing a 50-foot clearance. Subsequent labor disagreements further interrupted service at the port for long enough for carriers to halt container services, transferring cargo to other ports.

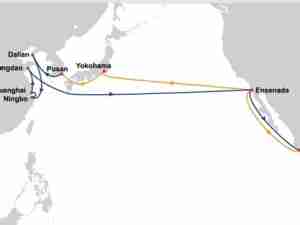

Seven U.S. ports (Los Angeles, Long Beach, Seattle, Tacoma, Oakland, Norfolk, and Baltimore) have been able to handle post-Panamax ships. Due to projects to deepen channels and remove air draught restrictions, they will soon be joined by Miami, New York/New Jersey, and Houston. Most improvements by these ports and others (Jacksonville, Savannah, Charleston) will bring water depth to the 50-foot range, allowing access for the larger vessels favored by alliances. However, choosing to upgrade infrastructure may be a difficult management decision for some ports, as capital costs are likely to require borrowing while returns from potential new services remain questionable for all but top tier ports.

The impact of changes in depth and other terminal improvements must be considered together with the relative importance of the port as a gateway to its region. As shippers seek consolidated service, a port with adequate infrastructure may still fall victim to competitive pressure should its market be one that can be efficiently served from a neighboring port.

Some ports may be able to avoid competitive disadvantages by engaging in regional partnerships. The Ports of LA and Long Beach have long participated in joint marketing to highlight the attractiveness of the overall San Pedro Bay gateway.

The Northwest Seaport Alliance between the Port of Seattle and Port of Tacoma, which has its "soft start" this month, will go even further. The Seaport Alliance will be formed as a Port Development Authority (PDA) -- a jointly owned, governmental entity, but with each port retaining its existing governance structure, ownership of existing assets under Seaport Alliance management, and obligation to repay debt to its bondholders. The Seaport Alliance seeks to unify management and operation of both marine ports' cargo to improve the Seattle-Tacoma gateway's competitive position in the container industry, avoiding duplicative capital investments, and harmful pricing dynamics.

Regional cooperation between ports in close proximity (including the Ports of Savannah and Charleston and Port of Fort Lauderdale and PortMiami) is potentially beneficial. However, there are likely many political and operational hurdles to pursuing such cooperation.

Ports with the right combination of location and infrastructure are best positioned to benefit from volume and revenue growth going forward. Ports with modern infrastructure but not located in geographically attractive areas could fall behind during these transitions, perhaps just as much as ports with inadequate water depth and landside infrastructure. Any port that loses market share as alliances shift cargoes may find it difficult to recover quickly, given the longer term nature of contracts between ports and shipping lines. However, smaller and mid-sized ports play an important role in specialized markets. Ports that serve local import/export demand or service specialized industrial centers are less exposed to competitive pressures since their volume drivers are not linked to fungible discretionary volumes.