You’d hardly know it from a scan of industrial news these days, but not all conglomerates are bad. Case in point, 3M Co.

The maker of everything from Post-it notes to dental varnish reported fourth-quarter and annual earnings on Thursday that exceeded analysts’ estimates, after backing out a charge related to the recently passed U.S. tax legislation. Organic revenue climbed 5.2 percent for the full year, as sales rose at every single one of 3M’s businesses and in each of its geographic areas. That’s remarkable, particularly a day after General Electric Co. —generally a hot mess these days—said its revenue excluding the impact of currency and M&A was flat last year as declines at certain parts of its industrial mishmash overwhelmed good news elsewhere.

At a time when industrial breakups are a hot topic and more companies are succumbing to a rethinking of their structures, 3M not only has managed to avoid activist pressure, but it’s also generally skirted speculation about a split. It’s proof that investors will tolerate—and even embrace—a diverse amalgamation of businesses as long as the combination makes sense, is well-run and management proactively lets go of the laggards.

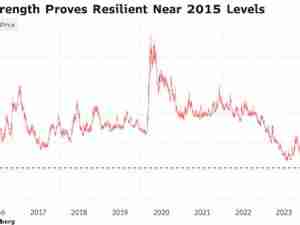

It’s hard to complain about a total return of more than 335 percent over the last decade—more than double that of the S&P 500. Even after last year’s 35 percent gain, 3M is exceeding the returns for a group of industrials on that index so far in 2018. That outperformance is based on a consistent track record of improving already high margins and a rarely shaken pattern of expanding organic sales. Not all of 3M’s businesses always do well, but the problems usually don’t overwhelm the whole, and that is the mark of a conglomerate that deserves to hold onto its structure.

3M increased its guidance for 2018 on Thursday because of the tax overhaul, helping to make up for a somewhat mediocre previous outlook it announced in December. The company’s 2016-2020 plan calls for a 2 percent to 5 percent increase its organic revenue. Thanks to its strong 2017 results, it’s on track to handily meet that goal.

A key reason the conglomerate structure works so well for 3M is that its business mix isn’t as random as it appears at first glance. The company’s customer base of consumers, automotive manufacturers, health-care companies and factory managers would be unlikely to convene anywhere except a highly eccentric cocktail party, but its products are unified by the underlying science and innovation. 3M sells transparent polyester double-sided medical tape, specialty high-temperature masking tape and good old Scotch tape. At the end of the day, they are all a type of adhesive.

In other words, you don’t need some grandiose vision to understand how 3M’s businesses fit together. Compare that to GE, which justifies having a health-care, power and aviation business because they are all considered core infrastructure that the world needs. That’s true, but it has never made much sense to me that a country would turn to GE for its power generation needs because a hospital bought an MRI machine from the company. Roads are also considered essential infrastructure, and you don’t see GE buying a paving company.

That’s not to say 3M can’t still do some pruning. The company has divested $2 billion of businesses over the past few years, including its communications-markets operations, which it agreed to sell to Corning Inc. in December. Another potential contender may be all or part of 3M’s consumer unit, which could be at risk of margin pressure amid the rise of e-commerce. That business had 1.7 percent organic sales growth in 2017, making it the only one out of 3M’s five main divisions to fall short of its long-term goals last year.

But the company—rather than an activist—will likely be the one to make the call on which pieces of its conglomerate empire stay or go.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of Bloomberg LP and its owners.