In mid-April, executives from foreign business chambers descended upon the home of an Indonesian minister to call for the removal of a new imports rule, a sign of the private sector’s increasing consternation over the government’s trade policy.

Representatives from seven business councils warned Coordinating Investment and Maritime Affairs Minister Luhut Panjaitan that Indonesia could damage its economic credibility with the recently implemented rule that effectively restricts imports of about 4,000 products, according to people familiar with the discussions.

They found a sympathetic ear in Panjaitan, an influential member of the government known for his economic pragmatism. The minister rang another cabinet colleague during the one-hour meeting to berate him and question the rationale of such a policy, laying open the differing positions within President Joko Widodo’s team on openness of trade.

The episode reveals how the contentious rule is testing the extent to which Indonesia is willing to hold on to its protectionist stance, as Jokowi — as the president is known — prepares to hand over power to President-elect Prabowo Subianto in late October. The tough trade bans that have become a hallmark of the current administration, enabling Jokowi to bring in nickel refining facilities and deter companies from stockpiling palm oil. But it is also leading to snarls in local manufacturing industries.

“Indonesia needs to fundamentally rethink the coherence of its trade policy within the context of its broader ambitions,” said Rahma Alifa, an analyst at BowerGroupAsia Indonesia. “Striking a balance between ensuring export-import flexibility and fostering innovation is critical.”

Panjaitan’s office didn’t immediately respond to a Bloomberg News request for comment.

The rule imposed in March was intended to spur more domestic production by making it harder for companies to import goods including laptops and raw materials like hazardous chemicals. The move has instead ignited furor among both local and foreign business communities, especially as it covers about 70% of goods traded domestically, Indonesian business chambers have said.

Global Supply

Local LG Electronics factories are struggling to get components needed to make washing machines and televisions that would be exported to South Korea, Luhut was told at the meeting, according to the people, who asked not to be named discussing private matters. LG Electronics didn’t immediately respond to a request for comment.

The rule isn’t helping Indonesia’s efforts to play a bigger role in the global supply chain, a representative of the Korean Chamber of Commerce and Industry told Panjaitan, the people said.

At the meeting, Panjaitan assured the business leaders that he will work to revert the new regulation to the old system. A few weeks later, Coordinating Minister for Economic Affairs Airlangga Hartarto told some of the business chambers’ leaders that the rule could be reversed by the year-end or early next year — effectively passing the burden to Prabowo’s incoming government.

“Indonesia wants to adjust its policies so that the global economy and supply chain finally play the tune that Indonesia is also composing,” said Achmad Sukarsono, a Singapore-based associate director at Control Risks, with a focus on Indonesia.

The rule isn’t meant to burden companies, but to reduce rising imports to facilitate the development of domestic industries, the trade ministry said in response to questions. The Korean Chamber of Commerce and Industry and Hartarto have yet to answer separate requests for comment.

Manufacturing Slump

Jokowi is shunning what he sees as an overly open economic model that he has blamed for undercutting Latin America’s growth prospects. Instead, he seeks to push Indonesia up the global value chain by courting investments while forcing companies to set up onshore if they want to tap the country’s natural resources or market goods to its 280 million people.

Prabowo has signaled he will maintain that stance. The president-elect has already said that all mobile phones sold in the country should be made locally.

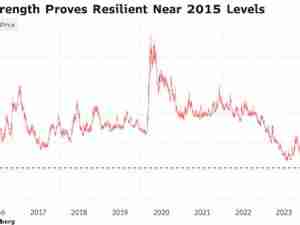

It’s a risky move that could hurt the country more than benefit it. The World Bank has cautioned that Jokowi’s protectionist stance has left the country marginalized by global supply chains and are hampering its manufacturing sector. Manufacturing as a proportion of Indonesia’s GDP slipped to 18.7% last year, from 21.1% in 2014 when Jokowi took office.

“Jokowi and later Prabowo also understand that they have the upper-hand in deciding trade rules in Indonesia as the country is the bright spot of investment in this otherwise challenging world that is growing slower than Indonesia,” Sukarsono said. Still, “if all investors are discouraged and ready to abandon Indonesia, officials will get the message and change the rules.”