A recent directive by Saudi Arabia’s Ministry of Energy asking the world’s largest oil and gas operator to maintain its maximum sustainable capacity (MSC) at 12 million barrels per day (bpd), instead of increasing it to 13 million bpd as previously planned, has fueled a wave of uncertainty and, to a large extent, an overreaction in the market around the continuation of upstream activities in the region.

With about 3 million bpd of existing surplus capacity, Saudi Arabia will continue to play an active role in balancing the market, with the announced pause removing a large chunk of its capital investment commitment at a time when drilling and completion costs remain high as supply chains remain under strain.

Rystad Energy explores the announcement and how it affects offshore expansion plans. It also adds some context around the current cost inflation challenges and the uncertain demand environment.

Saudi Arabia announced the MSC expansion plan to 13 million bpd in the third quarter of 2020 as global oil markets grappled with the disruption caused by the Covid-19 pandemic, while other operators went back to the drawing board revisiting their upstream investments amid a shift in focus to the energy transition mandate.

Saudi Aramco’s expansion plans gained momentum in 2021/22, when the supply crunch gave rise to a sticky underinvestment thesis and led to OPEC+ member nations to briefly reach pre-pandemic production levels.

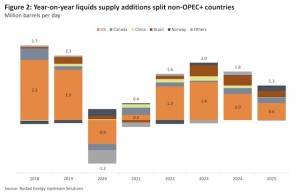

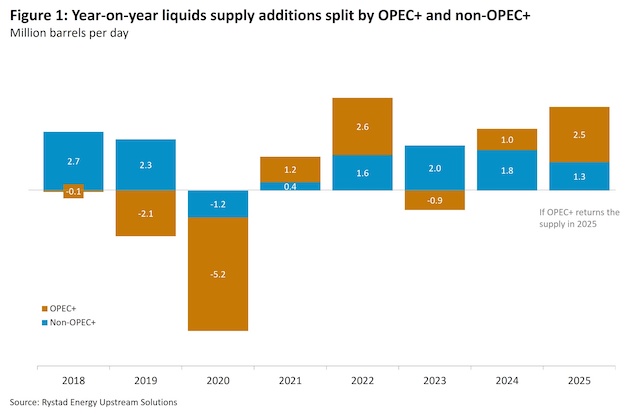

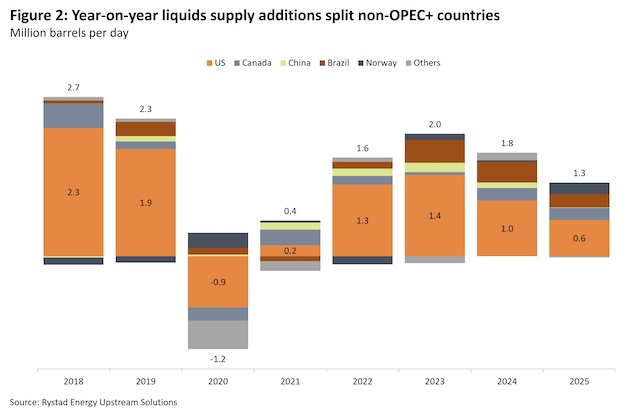

Shortly after, output rebounded from the non-OPEC+ members, particularly from nations beyond the US, prompting the OPEC+ producer group to essentially lower their quotas and revive a phase of cutting supply.

Rystad Energy sees an active and sustained role of OPEC+ interventions to ensure market balance.

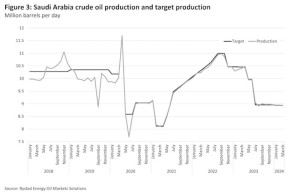

In the ongoing phase of cutting supply, Aramco has taken the extra step of announcing additional cuts on multiple occasions, essentially acting as a glue between supporting prices amid a weak consumption outlook, while other OPEC+ members actively debate individual reference levels and quotas.

The most recent cuts put Aramco’s production at about 9 million bpd, leaving about 3 million bpd as surplus capacity out of the regional total of over 5 million bpd, with the rest primarily coming from the UAE.

On the non-OPEC+ front, supply additions have continued to surprise, beating the upside potential by adding an average of 1.8 million bpd of liquids between 2022 and 2024, primarily from the Americas, including a more disciplined US unconventional sector and Canada, as well as Brazil and Guyana.

The demand front saw a massive slump during the Covid-19 pandemic, and while it has recovered, some sectors such as passenger transport and aviation are trailing, with an uncertain outlook for the future.

Coupling the supply additions with demand in a scenario where OPEC+ moves away from its supply cuts in 2025, Rystad Energy estimates an annual stock build of about 2 million bpd during 2025-2027.

In such a case, either supply would have to go down or prices will be under pressure.

Given this backdrop, the role of the core OPEC+ member nations, including Saudi Arabia, will evolve from fulfilling demand during a supply crunch to sustained cut management looking at a bearish market, starting as soon as next year.

Under such evolving markets, the mandate to rush for an additional 1 million bpd of capacity, especially in the inflated cost environment and the kingdom’s gas and alternative energy ambitions, could certainly warrant a pause.

Recent reporting and capacity expansion plans

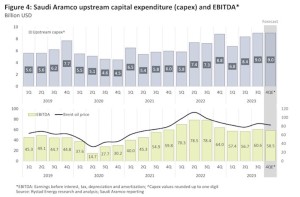

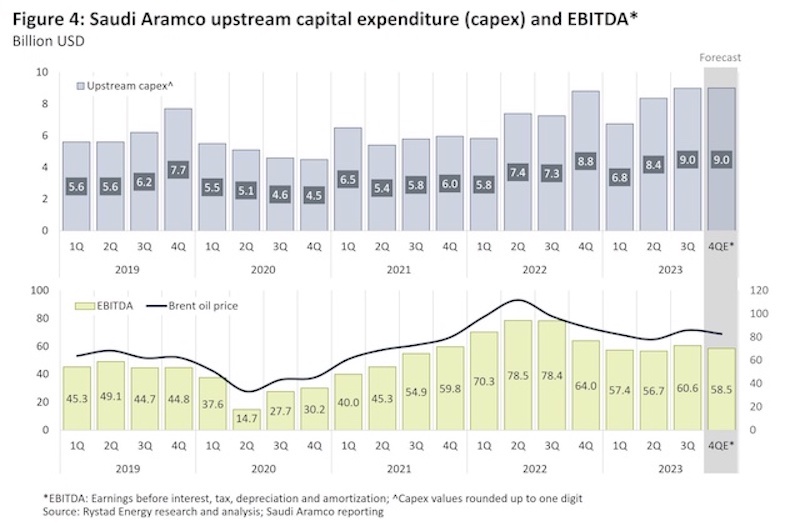

Aramco guided a total capital expenditure (capex) budget of $48 billion-$52 billion in 2023, with upstream estimated at $40 billion.

Aramco reported $174.7 billion of upstream earnings for the first nine months of 2023, a 23% year-on-year reduction.

This was primarily driven by a fall in liquids supply on account of the OPEC+ quotas, contributing 16.5%, and Brent price weakness at 12%.

Aramco also reported $24.1 billion in upstream capex for the nine months to 30 September 2023.

Rystad Energy estimates that Aramco’s upstream financials will end the year with upstream earnings of around $230 billion and capex at $33 billion.

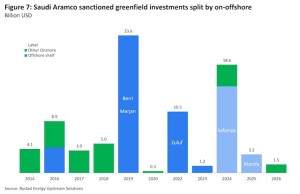

Aramco is largely focusing on offshore oil and gas expansion projects, such as the onshore Dammam and offshore Berri, Marjan and Zuluf greenfield developments.

On gas, processing capacity expansion at Hasbah and Hawiyah, and Jafurah unconventional remains at the forefront.

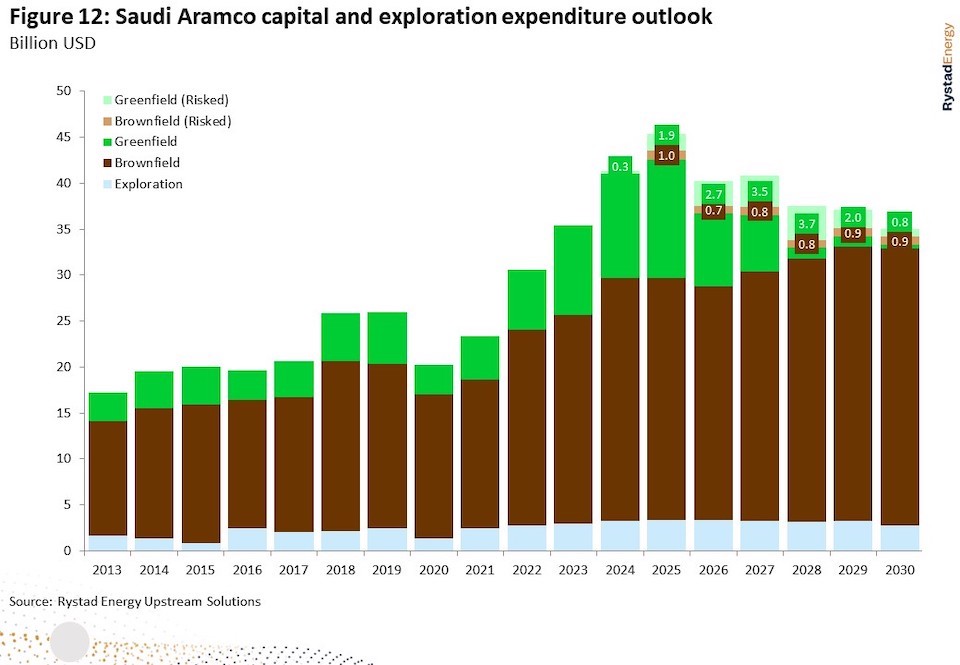

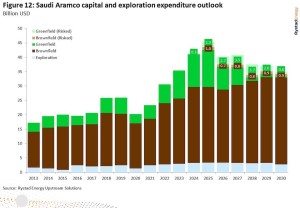

Before the revised mandate, Aramco planned to increase its capex until the mid-2020s.

We still see a growth in capex in 2025 with ongoing oil and gas expansion activities picking up in 2025, peaking at close to $40 billion.

We see a drop during the 2026 to 2030 period, averaging about $35 billion.

The incremental capacity developments are crucial for Aramco’s capex trajectory.

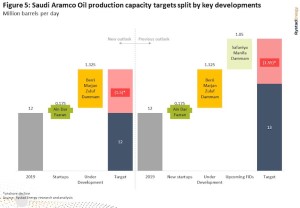

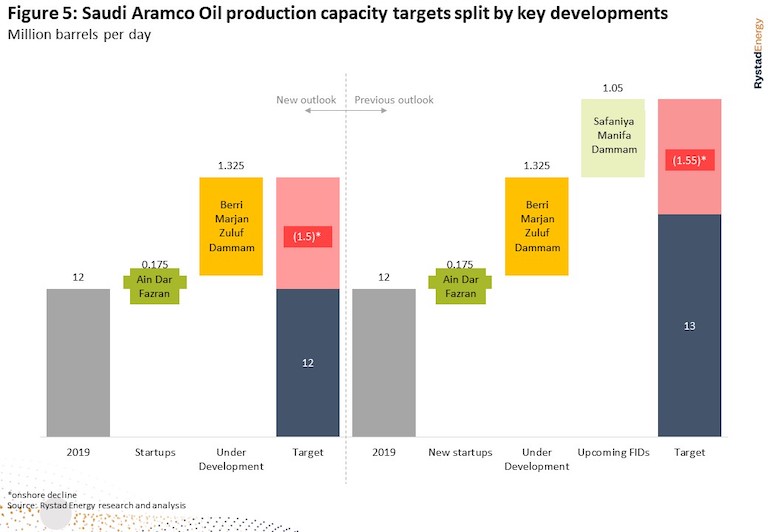

Aramco was aiming for an oil production capacity of 13 million bpd by 2027 – breaking it down to 12.3 million bpd by 2025, 12.7 million bpd by 2026 and finally 13 million bpd.

Aramco plans to increase its capacity by adding new offshore developments and arresting the decline from its onshore oilfields.

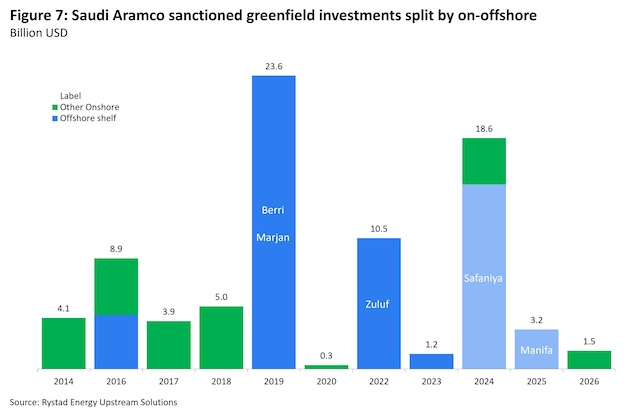

Key offshore projects that are under development include Berri (250,000 bpd), Marjan (400,000 bpd), and Zuluf (600,000 bpd) – together worth $35 billion in greenfield investments.

The fields currently under development are estimated to come online in 2025 and 2026, adding a cumulative 1.25 million bpd of capacity.

These three projects alone could take Aramco’s capacity to 13 million bpd in theory.

But just before the revised capacity mandate, Aramco was nearing workscope awards for Safaniya, followed by Manifa, both heavy cost intensive offshore developments, adding 1 million bpd capacity at a cost of $17 billion in greenfield investments.

Further developments on the horizon were planned at Marjan and Abu Sa’fah.

Looking at the upcoming developments in the context of future targets and onshore decline, the 2.25 million bpd addition was targeting a 1 million bpd capacity increase, leading to 13 million bpd of overall production by 2027.

This implies that over 1 million-1.25 million bpd of onshore capacity decline had been considered.

Now with the revised 12 million bpd outlook, the role of Berri, Marjan and Zuluf becomes crucial as they will replace the declining onshore capacity.

Therefore, we do not anticipate any immediate cancellation of the already awarded engineering, procurement and construction (EPC) and jackup contracted work scopes as these are gearing towards ensuring a sustained 12 million bpd capacity up until 2026–2027.

However, the surplus capacity additions from Safaniyah and Manifa could be paused, along with a further expansion at Marjan and Abu Sa’fah.

Saudi Grade implications

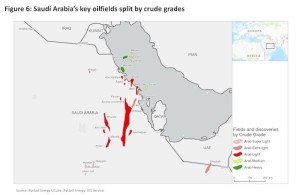

Increased offshore volumes will also mean that the share of heavy grades in the Saudi oil mix will increase.

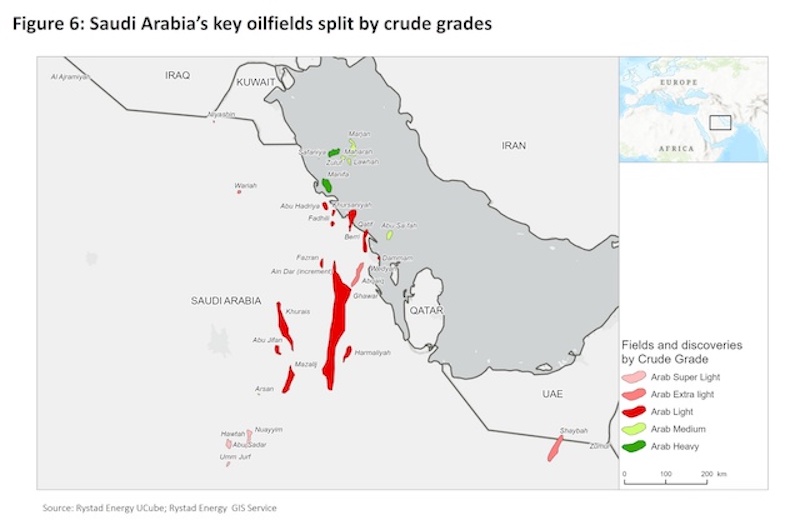

Saudi Arabia currently has five crude grades – Arab Super Light, Arab Extra Light, Arab Light, Arab Medium and Arab Heavy.

Onshore fields produce the majority of the lighter grades, while offshore fields produce the medium to heavy grades.

Aramco’s oil production from lighter grades and their share has remained between 66% and 70% over the last five years.

As per its 2019 prospectus, Aramco reported about 47.4% of its remaining resources in the lighter grades, followed by 17.7% in Arab Medium and 34.9% in Arab Heavy.

Output from offshore fields producing medium to heavy grades is capped by limited capacity.

In the absence of any offshore expansion, the country’s overall production is at risk of declining as the remaining reserve base cannot support the current split for long.

Therefore, a continued push in the offshore is required to maintain Aramco’s surplus capacity.

Also, despite the pause, a further decline from onshore fields will require incremental, let alone continued, offshore investments.

Upon inspecting recent and upcoming startups (2018-2026), we see that most focused on Arab Light developments at Khurais, Harmaliyah, Ain Dar, Fazran, Dammam and Berri, followed by the Arab Medium Marjan development, and the Arab Heavy Zuluf development.

With China and India set to increase their refinery capacity and stagnant South Korean capacity, Asian runs are forecast to increase.

Upcoming heavy grade supply from Aramco will see competition from Venezuela, Iran, Canada and Iraq, giving tough competition to similar quality Saudi crudes.

Impact on offshore jackup activities

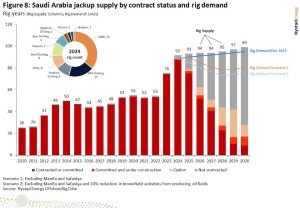

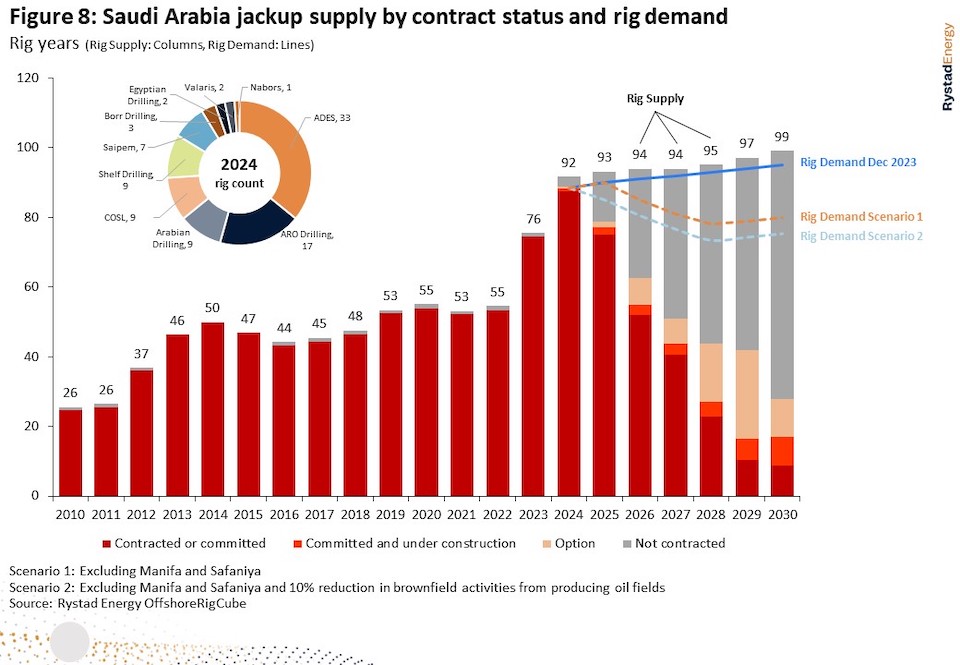

Saudi Arabia’s jackup rig supply has doubled compared to the 2013-2018 period (Figure 8).

The world’s largest oil and gas operator currently has 91 jackups under contract commitments which equates to just over 357 rig years-worth of remaining firm backlog and holds 70 rig years-worth of unexercised options.

In the previous three years, the national oil company (NOC) hired 87 jackups on either new co

Late last year, Saudi Aramco canceled a tender for up to five jackups to work under a lump sum turn key contract basis as they could not agree on the terms.

Other than exercising open options or extending contracts for rigs already under contract, incremental demand out of Saudi Arabia has slowed compared to the previous three years.

Excluding the contract bonanza of 2022, awards from the company averaged about 15 per year for the past 10 years, including new mutual, extensions and exercised options.

Before Saudi Aramco’s announcement this week, Rystad Energy expected jackup demand to grow gradually to 95 rig years by 2030, driven by the large offshore expansion projects (Zuluf, Berri and Marjan), before maintenance drilling (infill) and workovers helped drive sustained high activity levels.

Rystad Energy estimated that drilling at the not-yet-sanctioned Safaniya and Manifa would have begun in 2026-2027 and account for around 15 rig years combined each year from 2027-2030.

In the event production targets are not reset to 13 million bpd and these projects do not move forward, the impact could result in a decrease in jackup demand of more than 10% from 2025-2030.

Rig demand on brownfield activities will also likely be impacted from 2025, since near-term projects are already covered by firm drilling programs and the planned, but not-yet-sanctioned Safaniya and Manifa projects were not forecast to require rigs before 2026.

In a scenario where brownfield activities from producing oil fields are cut back 10%, cumulative rig demand between 2025-2030 could drop by more than 15%.

Rig demand on gas fields, on the other hand, will likely go ahead as planned.

While Saudi Aramco could terminate existing contracts, we see it as more likely that it would suspend contracts should it find itself with excess capacity as it did during the Covid-19 pandemic.

The other possibility is that some jackups may not be awarded extensions. Between 2024 and 2028, there are some 80 jackups set to roll off contract should no extensions be awarded, or no options be exercised. However, this is an unlikely scenario.

The pie-chart on Figure 8 shows the breakdown of offshore drillers in Saudi Arabia in 2024.

The top slots are currently held by Middle Eastern players ADES, ARO Drilling and Arabian Drilling, with these companies occupying around 65% of the market share, with the rest scattered between different international drilling companies including Shelf Drilling, China Oilfield Services Ltd, Saipem, Borr Drilling and Egyptian Drilling.

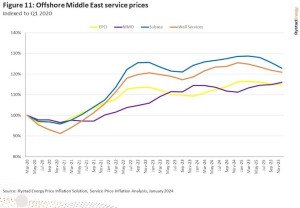

A strong global comeback in oil demand after the pandemic and the significant rightsizing of capacity in the supply chain since 2015 have given service companies bargaining power once again.

As some constraints in the oil markets did not play out as expected, Saudi Arabia can use production levers as a better way to time investments relative to pricing levels in the supply chain.

One segment which has felt the effects of price inflation is the shallow water drilling market in Saudi Arabia.

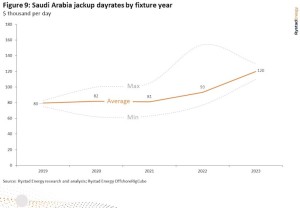

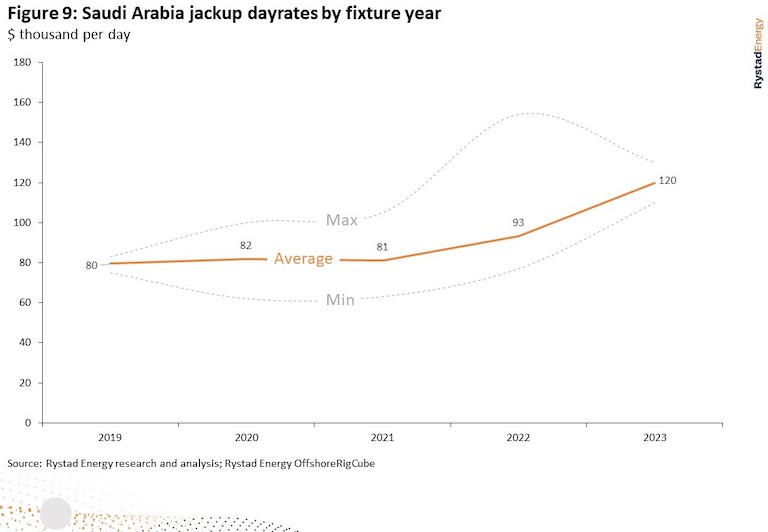

Rig demand growth following the previously announced expansion plans caused jackup dayrates to increase from around $80,000 per day to about $130,000 per day over the last several years.

Inflated cost environment

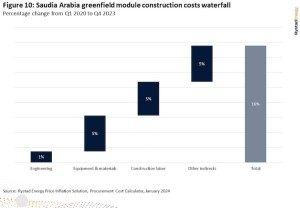

Since Saudi Aramco’s announcement of its strategic growth initiative in 2020, service costs have surged with little signs of cooling.

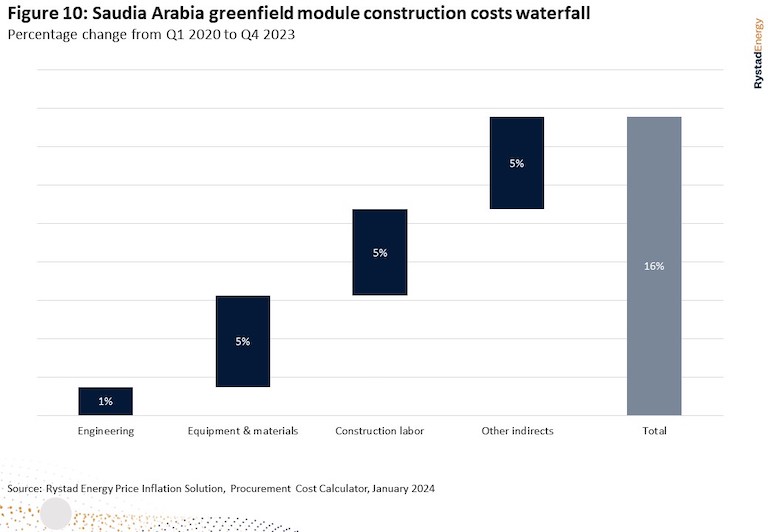

Local module construction costs alone have seen a near 15% increase since the announcement, with continued growth expected over the next several years.

This rise has not been concentrated to just one element of the EPC, but has increased engineering, procurement and construction costs, including both direct and indirect components.

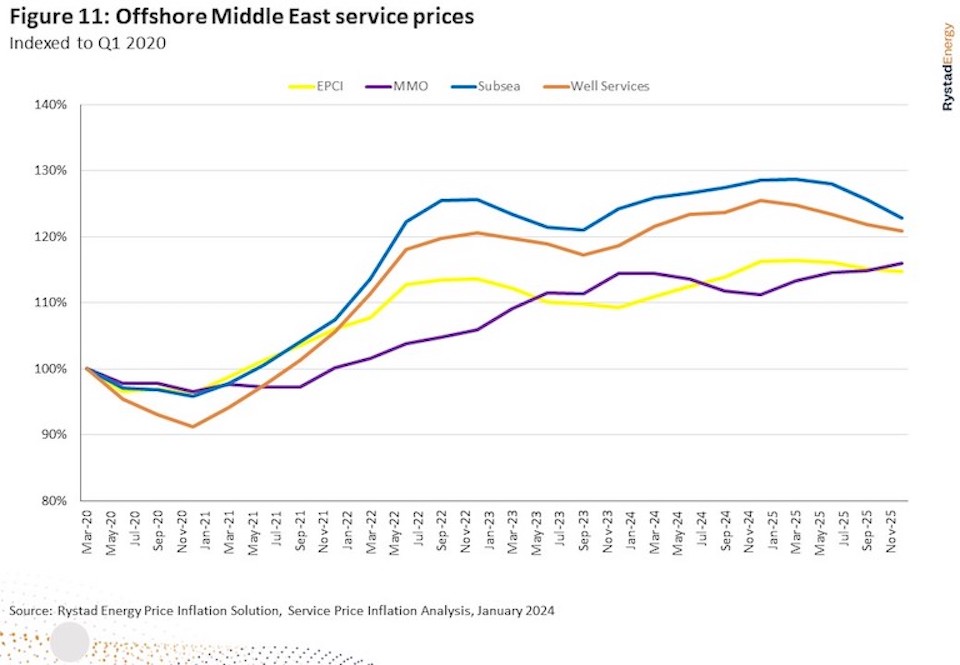

The $20 billion of investments Saudi Aramco would be making, primarily for offshore work, would force them to place contracts through an up-cycle of offshore service prices.

Inflation has hit all aspects of its growth portfolio, from rig rate increases and subsea equipment price surges through surface facilities EPC and MMO costs rising.

These service price pressures could also be exacerbated by other industries increasing manufacturing orders in China, the EU and the US.

While the upstream industry alone will provide enough local and global demand to support elevated offshore service prices, the risk from other industries is hard to ignore and one that must be accounted for here.

With about 3 million bpd of surplus capacity, Saudi Arabia will continue to play an active role in balancing the market.

Strong supply growth from non-OPEC+ countries, along with a transition in demand across different segments, will collectively require core OPEC+ members, including Saudi Arabia, to play a sustained balancing act in the near term.

That scenario warranted a response to the million-dollar question of proceeding with its plan to boost capacity or taking a pause till inflation cools down.

Rystad Energy estimates that the revised mandate will reduce capex requirements by $20 billion – $15 billion from greenfield offshore oil developments, and the remainder from the potential downside in long-term offshore brownfield activities, as rig contracts start to roll off during 2024-2028.

In terms of core areas, the strategy would be largely unaltered – a focus on gas expansion, ensuring offshore oil supply additions to cover for the legacy onshore decline, and onshore oil production maintenance activities.