The UK will increase power sales to the continent this winter as a slump in carbon prices makes it cheaper to produce electricity at gas and coal plants.

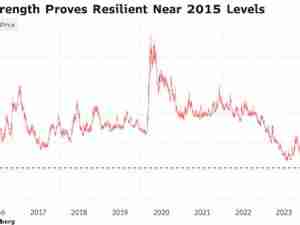

The price gap is a consequence of the UK government’s recent decision to ease the burden on emitters as part of market reforms. A glut of permits has sent carbon prices down 50% this year, compared with less than 3% for European Union futures. That means a competitive advantage for the UK’s fleet of power stations over those on the continent.

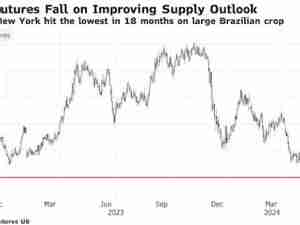

Costs are likely to remain lower in the UK, prompting more exports along subsea cables to France, the Netherlands and Belgium. While Britain will remain a buyer overall, net imports to the island are seen just below four terawatt-hours in the first quarter, or half compared with a year earlier, S&P Global Commodity Insights said, without breaking out actual exports.

“Europe’s gas plants are normally dispatched before the UK, but that order has shifted,” said Jean-Paul Harreman, a director at industry consultant EnAppSys BV. “That means Britain will likely be sending more power than usual to its neighbors on the continent this winter, or importing less.”

The carbon price is meant to be a deterrent to pollute. For each ton of emissions released, factories and fossil-fuel power plants need to buy a permit. Those, along with the price of the fuel, are key components in generation costs.

In a paper detailing its decision in June to release extra permits, the UK government’s Department for Energy Security and Net Zero said it was to allow the market participants “time to adapt” and “smoothing” the transition to net zero.

But after the slump in UK prices to about £37 per ton, allowances are trading at about half the level of those on the continent. The discount is near its widest since the British system split off from the EU more than two years ago.

“One thing that is at least clear is that UK imports would be higher if it were not for this price difference in carbon,” said Fabian Ronningen, a power analyst at Rystad A/S. Britain might even be a net exporter this winter if continental supplies start to get more scarce, he said.

That means it might make more sense for traders in France, for example, to import from the UK and pay an extra fee to transport electricity across interconnectors than to pay domestic plants to generate.

Excluding power flows from Norway, where cheap hydropower is the dominant source, Britain will be a net-exporter this winter, according to S&P Commodity Insights.

This week, UK power prices for the first quarter of next year traded about £124 per megawatt-hour, about 2% lower than the equivalent French price of €147.

While more demand from abroad would be a boost for generators including commodities giant Vitol Group and German utilities RWE AG and Uniper SE, it’s bad for the pollution at home. Emissions from the UK power sector reached a six-month high last week, according to BNP Paribas strategist James Huckstepp.

If supplies are tight at times this winter, scheduled exports could lead to higher prices in Britain. National Grid Plc said in its early winter outlook it expects a more comfortable winter this year with more grid-scale batteries, which help deploy renewable power, widening the supply buffer.

Investors are asking for clarity on how the government intends to regulate carbon prices in future. It’s a price driver for building energy storage systems, which just like gas plants are flexible and can be called upon at times of high demand.

“While we may see cheaper power from gas power plants this winter, the government needs to be clearer about the cost of carbon going forward,” said Tom Vernon, the chief executive officer of Statera Energy Ltd., which is developing gas-fired plants in the UK. “More clarity will provide more certainty on the long-term viability of these plants and of low-carbon assets like batteries.”