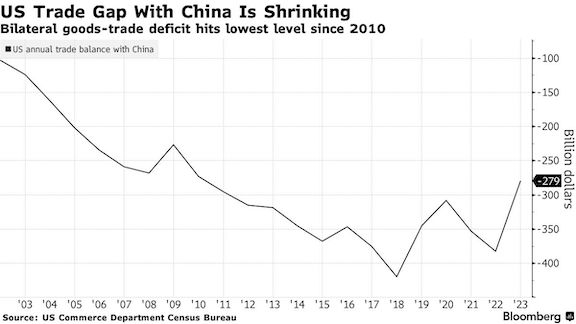

The US goods-trade deficit with China shrank to the smallest total since 2010 last year, reflecting a decline in imports from its geostrategic rival that will be welcomed in Washington.

The excess of imports over exports to China was $279 billion, US Commerce Department data showed Wednesday. As a share of GDP, the goods deficit with China came in at just 1%, the lowest level since 2002.

“The data for 2023 have confirmed that the geographical pattern of US imports is shifting away from China and toward other partners,” said Maeva Cousin, a senior global economist at Bloomberg Economics. “Tariffs since 2018 have been a major driver of these shifts, but we are now seeing some early signs that US trade diversification might be broadening to other categories as well.”

By contrast with the trend with China, the US goods deficits with Germany, Italy, the Netherlands and others soared to new highs.

Deficits also hit a record with Mexico, South Korea, Taiwan and India, underscoring the emerging shift in global trade flows as years of geopolitical tensions, rising tariffs and supply-chain snarls force a re-shuffling of manufacturing production around the world.

The shortfall with European nations threatens to meet with a response should Trump win re-election in November. His team is targeting the European Union for a potential slew of punitive trade measures designed to address long-standing grievances should he retake office, Bloomberg News reported.

A likely starting point in a second Trump administration would be the EU’s inclusion in a broad minimum 10% tariff, which would also be applied to China.

To be sure, the 2023 decline in imports from China can’t be pinned solely on tariffs and geopolitics alone. Fluctuating currencies, well-stocked US inventories and softer consumer demand also contributed. Production was also shifting long before the trade war, spurred by rising labor costs in China.

Another factor: the imposition of Trump’s tariffs likely led to US importers under-reporting how much they bought from China, according to 2021 analysis by Federal Reserve economists.