Three months ago, Ursula von der Leyen, president of the European Commission, announced — to much fanfare — a “Green Deal” to make the EU carbon neutral by 2050. Alas, a few things have happened since, including a pandemic and an oil shock. Together, these unforeseeable events cast doubt over the Green Deal just as it’s supposed to become legislation this year. The EU must ensure that the two new problems don’t exacerbate an even bigger one: climate change.

First the good news, such as it is. In the short term the coronavirus almost certainly reduces greenhouse gas emissions. The world’s biggest polluter, China, was the source of the outbreak and temporarily had to idle much of its industry. Many airlines are grounding their fleets, and people are also shunning other forms of travel as industry fairs and meetings are cancelled. Less kerosene and gasoline is being burned to carry people around, and less carbon dioxide is escaping into the air. But this reprieve is merely a one-off effect.

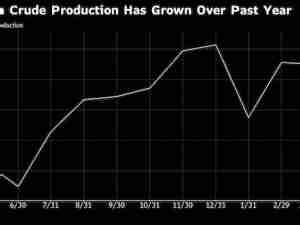

More important for the Green Deal is the effect of the crisis on energy costs. Less demand also means lower prices, which has strained relations between the major oil producing nations. Saudia Arabia and Russia are suddenly at each other’s throats, with the former dumping so much oil onto the global market that the crude price on Monday collapsed to its lowest level since 1991. It could stay dirt-cheap for some time.

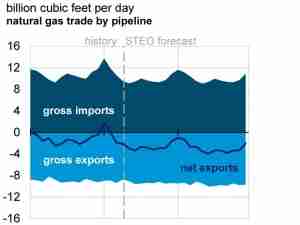

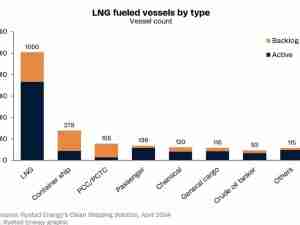

Gas prices have plummeted alongside those of oil. And these two fossil fuels are now making other energy sources less competitive. That is good if gas power plants drive out even dirtier coal-fired ones. But it’s bad when, in transport or heating for example, cleaner and greener alternatives lose attraction: fuel cells, say, or electric cars charged with power from the sun or wind. In green technology, innovation and adoption tends to accelerate when fossil-fuel prices are high, and to decelerate when they’re low.

Now take a closer look at the EU’s Green Deal. It’s a vast and complex package of measures, but it breaks down into two conceptual parts. The bigger one consists of various forms of direct state intervention in the market — ranging from subsidies to prohibitions and coaxing — to help technologies, investments and companies that are deemed “green.”

These projects just got, relative to their fossil-fuel alternatives, much more expensive for taxpayers, and much more invasive and distorting for market participants. To drivers refueling at the pump or homeowners installing a heater, the market’s price signal points in one direction, while EU policy points in the other. This won’t go well.

The Green Deal’s other part is much more promising, especially from a liberal (meaning market-friendly, not leftist) perspective. It involves expanding and tightening the EU’s existing emissions trading system, which relies on price signals and market forces to decide where in the economy it’s cheapest and easiest to cut emissions fastest.

In this system, the EU fixes the total quantity of carbon that can be emitted by certain industries, from cement and steelmakers to airlines and power plants, and gives out allowances. Companies that find ways to emit less, by investing in new technologies or processes, can sell their certificates to others who need more time. As the EU notches down the overall quantity, certificates gradually become scarcer and thus dearer, giving companies even more incentive to reduce or recapture their carbon footprint.

But the system has two big challenges. One is that the price of allowances, even though it’s gone up recently, is still far too low, currently about 23 euros ($26.1) per metric ton. The even bigger problem is that the system at present only covers sectors responsible for less than half the EU’s total carbon footprint. Among the most glaring omissions is the entire transport sector (meaning road, rail and water, not air).

Fortunately, the EU now has an ideal opportunity to fix that: It should, with haste, step in to extend the emissions trading system to the petroleum industry. With crude oil prices so low, consumers at the pump wouldn’t initially feel the difference. But as the oil and Covid-19 crises recede, the carbon price would bite just as it should, changing behavior and investment decisions throughout society.

Europe, like other parts of the world, has several big tasks in 2020. One is to beat the virus, another is to save the economy in the process, a third is to start rescuing our climate. If the European Green Deal fails, others, from China to India, won’t even think of emulating it. The eventual fallout from the coronavirus and the oil shock would then be planetary.