German Farmer Left Cold by Beer With Obama Shows TTIP in Trouble

By: Arne Delfs | Jun 01 2016 at 06:01 PM | International Trade

Wearing an Alpine felt hat and vest on a tour of his dairy pastures, Alois Kramer is hardly the stereotype of an anti-globalization protester.

He’s still hailed as one in the Bavarian village he calls home after challenging President Barack Obama over the benefits of trading with the U.S.

Kramer, an organic-milk farmer who met the president over beers during last year’s Group of Seven summit in Germany, says he wasn’t swayed then and is even more concerned now that the planned Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership, a pact to expand U.S.-European commerce, is a threat to his business.

“We here in the region don’t want to produce like in the U.S.,” Kramer, 47, said in an interview at his chalet-style home in Kruen, the village where he sat in the sun last year with Obama and Chancellor Angela Merkel for pictures that went around the globe. “I’m sure my discussion with the U.S. president would be even more controversial today.”

Kramer’s opposition to TTIP even after a personal chat with one of the world’s most persuasive political leaders illustrates the challenges of completing the deal before Obama leaves office in January. Coming from a political ally in a conservative heartland, Kramer’s stance reflects a growing backlash against the accord—valued at some $134 billion by the U.S. Chamber of Commerce—that’s adding to Merkel’s domestic headwinds.

“The huge level of skepticism in Germany is a decisive reason why the talks between the U.S. and EU may ultimately fail,” Holger Schmieding, chief economist at Berenberg Bank in Frankfurt, said by phone. “TTIP is the western world’s last chance to impose global standards,” and “sadly we’re on the verge of wasting it.”

Trump Pressure

Free-trade agreements are coming under pressure globally as surging populist sentiment feeds protectionist rhetoric. In the U.S., presidential hopefuls Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders have linked job losses to trade deals, casting doubt on the willingness of Congress to back the 12-nation Trans-Pacific Partnership while undermining moves to complete the bigger pact with the 28-nation EU. Hillary Clinton too has raised concerns about the Pacific deal.

For a summary of the trade battle in Congress, click here

In the German capital, Merkel sees tying up a deal in 2016 as imperative because political developments in the U.S. and in the EU might close the window for agreement after then, according to a person familiar with her viewpoint. Hence the chancellor won’t budge on her goal of completing a draft accord this year, and views the domestic debate on TTIP as increasingly hysterical, the person said.

“We’re just doing too well,” said Berenberg’s Schmieding. “We spend our time brooding over what bothers us without giving a thought to how we’ll earn a living in the future.”

Opponents of TTIP are focusing on plans to lower barriers in areas such as agriculture, services and food and environmental standards, creating an opening for products such as U.S. chlorine-washed chicken and hormone-treated beef. EU officials, who have been negotiating with the U.S. since 2013, dismiss the notion that the pact would lower food safety as a “myth.”

“We can’t cancel our principles,” EU Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker told reporters in Paris Tuesday. “So our negotiators know what concessions they can’t make.”

Quarter-Million Protest

Still, about 250,000 protesters marched against TTIP in Berlin’s government district last fall, underscoring the opposition to the deal in Europe’s biggest economy. Tens of thousands turned out again last month in Hanover when Obama and Merkel met at an international trade show to try to spur the talks.

Kramer’s family has been dairy farming in the region nestling among Alpine meadows and some of Germany’s most beloved mountain scenery since about 1500. He’s concerned that TTIP would kill centuries of tradition by flooding the European market with cheap dairy products, making his farm unprofitable.

Like many Germans, Kramer was shocked when leaked draft passages from the U.S.-EU talks emerged in May. Published by Greenpeace, the documents fed a sense of secrecy about the negotiations and revealed what was perceived as hard U.S. bargaining on items such as consumer protection. The environmental group set up a glass cube at the Brandenburg Gate in Berlin to provide public access to the documents.

‘Trade War’

EU officials said the Greenpeace leak exposed little that wasn’t publicly available and Merkel’s government pushed back, saying complete transparency would undermine EU negotiating tactics. That doesn’t convince Kramer, who sits on the town council for the Christian Social Union, the Bavarian sister party of Merkel’s Christian Democrats.

“The Americans are fighting with any means possible,” he said. “It’s just another trade war for them.”

For more on the U.S. politics of trade agreements, click here

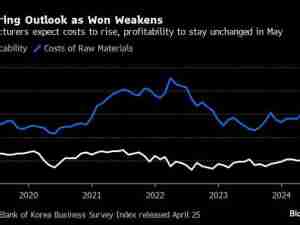

With populism rising on both sides of the Atlantic, creating the world’s biggest trade bloc is an increasingly tough sell for Merkel as opponents across the German political spectrum portray the deal as virtually dead. Only 17 percent of Germans support the planned pact compared to 55 percent two years ago, according to a Bertelsmann Foundation study published in April. Sigmar Gabriel, the Social Democratic vice chancellor, has said “it’s conceivable that the talks will fail” unless the U.S. makes concessions.

Trust Evaporating

Backed by business lobbies that represent global corporations such as Siemens AG, Volkswagen AG and thousands of export-oriented smaller companies, Merkel says a deal is possible without the EU rolling back a single rule, including on consumer protection.

Yet it’s precisely a trip to Vermont in 2001 that showed Kramer he doesn’t want U.S. production methods encroaching on Europe. He came away convinced that U.S. dairy farmers “don’t care how something is made” and only want to push out the final product.

A year on from the G-7, the table that he shared with Obama and Merkel stands outside the village hall with a photograph to mark the moment, an encounter he shrugs off as “not such a big deal.” For Kramer, the real legacy of that day is a deterioration of faith in all political leaders.

“We don’t trust our politicians anymore,” Kramer said. “Angela Merkel would sell us all to the Americans only to secure for herself the title of export world champion.”