Shrinking trade puts pressure on emerging market growth, investment

By: Reuters | Jul 23 2015 at 03:58 PM | International Trade

Falling exports are piling pressure on emerging economies, putting many of them at risk of a multi-year cycle of sluggish trade, economic growth and investment.

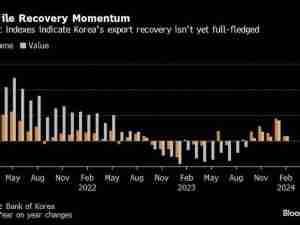

From Korean cars to Chilean copper, exports from emerging markets are declining year-on-year at the sharpest rate since the 2008-09 crisis, according to a report by UBS, while Asian powerhouses such as Korea, Taiwan and Philippines have posted five to six straight months of dwindling overseas sales.

On Thursday, South Korea posted its worst quarterly economic growth in more than six years and while many factors drove the print, slowing exports certainly contributed.

Initially blamed on wary Western consumers and China's reduced appetite for oil and cement, the trade slump is increasingly stemming from weaker intra-emerging market ties - the so-called south-south trade valued by the United Nations in 2013 at $5 trillion.

That's unsurprising - UBS estimates emerging markets' growth premium to richer peers as now being under 3 percent, the narrowest since 1999. And as consumption and investment fall in many countries, their imports too are shrinking.

"Any country that is relying on exports is going to have a very hard time," said Yu-Ming Wang, chief investment officer at Nikko Asset Management which manages almost $170 billion.

"The world's capacity to grow is more limited now. In the past decade, China created the equivalent of Germany, France and Italy, it can't do that all over again," said Wang. China's $9 trillion economy has expanded tenfold since 2000.

Just as China's rise since 1990 transformed swathes of countries, its gearshift to slower growth is hitting them on the way down, whether Latin American commodity exporters or Asian countries whose factories are part of its global supply chain.

China imports $50 billion a month less than during 2013 peaks while latest monthly exports were $26 billion off the highs at the end of last year. Latest data shows imports, often semi-finished goods for re-export, fell 15.5 percent in the first half of 2015 from year-ago levels.

Other factors include yen weakness that has made Japanese firms more competitive against Asian rivals and the erosion of emerging markets' productivity and currency competitiveness during the boom years.

That has encouraged "onshoring" - moving manufacturing back to the United States or Germany. And finally, U.S. imports increasingly consist of machinery and equipment that come from Germany or Japan rather than emerging markets.

"The world of exports is no longer beautiful," Thailand's central bank governor Prasarn Trairatvorakul said recently. "Although the United States is recovering, (we) should not expect... that it will import as much as it did before."

Prasarn warned that Thai growth may slow below 3 percent this year, as exports which amount to 75 percent of annual output may fall for the third straight year. In 2010, Thailand achieved a growth rate of 7.8 percent.

Domestic Consumers

Governments can offset the impact of falling exports by raising spending and cutting interest rates. But in countries where years of low borrowing costs have raised consumer debt levels, that strategy carries risks.

Record Thai household debt for instance is seen blunting the impact of rate cuts, with policymakers pinning hopes on a weak baht to spur exports.

In South Korea where households owe $1 trillion and spend a third of their income on debt payments, further rate cuts look tricky. It also means domestic demand cannot rise much to compensate for slower overseas sales.

Brazil, China, Singapore, Thailand, and Turkey were among countries where household debt is up more than 40 per cent since 2008, International Monetary Fund data showed last year.

"The EM domestic consumer is in trouble especially where they are highly levered as in Korea, Brazil or South Africa," said Kathryn Langridge, head of emerging equities at Manulife Asset Management.

She said these shifts are already re-shaping investment portfolios, with a skew towards markets like India where local demand, not exports are the main driver.

"Unless you have a brandname or something else that gives you pricing power, you are dead in the water in the export market. This is one reason why emerging markets have underperformed," Langridge added.

NN Investments has cut emerging equity positions further, its strategist Maarten-Jan Bakkum said, citing fears of a "multi-year downward trend" in EM growth.

Allowing more currency weakness and raising productivity may help. But most reckon the trade and consumption boom of the past decade won't be repeated.

Indeed the World Trade Organisation expects global trade growth to fall short of overall economic growth in coming years - a departure from the trend of recent decades.

So how should investors respond? Government bonds may be the answer.

"What emerging markets have is a bad income statement but a reasonable, if worsening, balance sheet," said Bhanu Baweja, UBS head of EM strategy.