Now that President Joe Biden has signed off on a law that could expel TikTok from the US market, Beijing must decide how best to retaliate over an attack on the world’s most-valuable start-up.

The legislation approved on Wednesday would give Chinese parent company ByteDance Ltd. nearly a year to divest the video-sharing platform before facing an outright ban. At a daily briefing hours before, China’s Foreign Ministry directed reporters to a vow by commerce officials last month to take “measures to resolutely safeguard its legitimate rights and interests.”

President Xi Jinping’s government has so far shown restraint in responding to a drumbeat of US trade curbs during a hawkish election season. The Communist Party’s moderation has been made easier by Biden’s choice of largely symbolic actions, such as tariffs on metals China exports little of to America.

Driving TikTok — or its Chinese owner — out of the US could challenge that calibration. Officials last year displayed their willingness to respond in kind to a US campaign to kneecap Beijing’s access to advanced semiconductors, for example, by launching a probe into American memory chipmaker Micron Technology Inc.

“China is keeping options open at the moment,” said Xiaomeng Lu, director of the geo-technology practice at Eurasia Group. But she said if TikTok exhausts its legal options and has to exit America, “some US tech brands could be at risk of becoming the collateral damage of this tit-for-tat cycle.”

Beijing’s internet restrictions have already forced most American social media firms out of the Chinese market, such as Meta Platforms Inc. and Snap Inc., narrowing the list of potential targets for a tit-for-tat response. Any Chinese action would likely try to avoid inflicting harm on its own economy, as policymakers battle a property crisis that’s weighing on growth along with weak domestic demand.

The ratcheting up of trade tensions comes as Secretary of State Antony Blinken arrives in China this week to press US concerns about Chinese companies’ support for Russia’s war machine. The Biden administration has threatened Beijing with sanctions on its banks if they bolster the Kremlin’s campaign in Ukraine, a move that risks hurting US cooperation with China in other geopolitical hot spots such as the Middle East and North Korea.

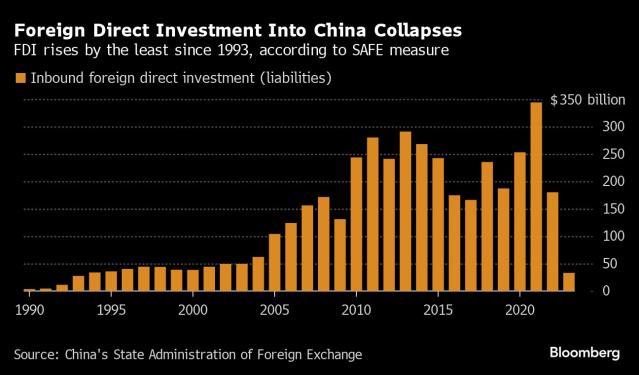

Another consideration would be the optics, after foreign investment into China slumped to a 30-year low in 2023. Xi traveled to San Francisco to woo American CEOs in November and rolled out the red carpet for executives in Beijing this year, as officials ramp up efforts to boost sentiment.

“If they sanction US companies this could intensify American firms’ concerns about operating in there,” said Wei Zongyou, a professor in American security and foreign policy at Fudan University in Shanghai. “That means the likelihood of taking further restrictions and sanctions on companies in China is not that big.”

Still, China has other, less well-documented weapons at its disposal — including restricting US access to the world’s No. 2 economy, a persistent point of friction between Beijing and Washington.

Chinese agencies and government-backed firms ordered staff to stop bringing iPhones and other foreign devices to work last year, in an unprecedented prohibition that’s likely to clip Apple Inc. sales in China. Tesla Inc.’s electric vehicles are already subject to restrictions in government compounds, due to concerns about data being collected by the cameras built into the cars.

The danger is Beijing will ratchet up semi-official moratoriums on the use of American hardware, potentially pressuring companies like Microsoft Corp. and Intel Corp. Many major firms operate influential lobbies in the US and have been known to oppose broader American sanctions for fear of losing market access.

Intel was forced to walk away from its $5.4 billion takeover of Tower Semiconductor Ltd. last year after failing to win Chinese regulatory approval in time, a move seen by some in Washington as a response to Biden’s sweeping chip curbs.

While Xi has a long-term objective for tech independence, alienating foreign firms in that sector would only slow China’s development, according to Li Mingjiang, associate professor at Nanyang Technological University’s S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies. “What China wants now is to reduce tech decoupling with the US,” he said. “Punishing a US tech company will not be helpful for this purpose.”

The most likely immediate action China will take is trying to prevent TikTok being sold to an American entity. Beijing could leverage export controls it imposed in 2020 over content-regulation algorithms, which are the heart of the platform’s global success — a move that would force ByteDance to exit the US market rather than acquiesce to a sale.

The company itself has said it would take legal action if the bill is signed into law. That would see the platform rely on the First Amendment argument, as it has done to fend off a state ban in Montana, in an effort that could span years.

In another twist, Biden’s challenger Donald Trump — who previously tried to ban the app while in the White House — could end up giving the platform a reprieve, if he wins the November election. The former US president has raised concerns banning TikTok would elevate its rival Meta.

For now, Beijing has to wait to see how the US election plays out, said Zhu Feng, executive dean of Nanjing University’s School of International Studies, highlighting that the legislation has an impact on both nations.

This kind of ban doesn’t only hurt China, he added, “it hurts the 170 million American users of this app.”