The marine chassis business faced some serious challenges during the post-COVID surge. And for an industry that had gone from being “ocean carrier-centric” for four decades to an intermodal equipment provider (IEP) in a mere 15 years, the kinks in the system were exposed. A new era has begun for chassis providers but it is still a work in progress.

Under the Box. A little over a year ago, most of the headlines about the chassis business revolved around the shortage of chassis for drays — trucks moving ocean containers to and from ports. For most of the public, a marine chassis is something with wheels that is stuck underneath a shipping container that you rarely notice unless you are stuck in a traffic jam next to a truck working on a dray.

But the idea that the chassis was critical to the movement of the boxes began to hit home with the general public as talk of the problems with the supply chain entered the mainstream news coverage during the COVID-19 crisis. No chassis, the box doesn’t get moved to the distribution center and Halloween costumes become Christmas gifts.

To be clear, a majority, amounting to 56% of the chassis, are for domestic operations but the other 44% of largely marine chassis are involved in carrying ocean containers and thus their utilization is inherently connected to ocean container terminal traffic.

Marine chassis utilization during the post-COVID surge was over 90% and shortages contributed to disruption in the supply chain… and a lot of unhappy customers. Although it was a country-wide issue, the chassis shortage problem begins and ends with port congestion. Export containers couldn’t get into the terminals [largely because surging imports were the priority], thus the boxes on the chassis were unable to be grounded on the terminal tarmac. Consequently, the chassis couldn’t be turned and reintroduced back into circulation and without a free flow of chassis, the demand for chassis ratcheted up throughout the supply chain.

Many in the industry believe there was already a shortage in the chassis fleet and need of an overhaul before the post-COVID surge began, and the freight surge exacerbated an existing problem.

This is not to say there wasn’t an effort already underway to restock the chassis fleet. [For example, Direct ChassisLink (DCLI), one of the largest intermodal equipment providers (IEP) in 2020 invested $85 million in a chassis refurbishment program. And announced in 2022 that it had invested $1 billion in additions and enhancements. Another major IEP, TRAC Intermodal wrote it had invested a billion dollars since it began renewing and growing the chassis fleet in 2015.]

But fleet investments aside, there was a lot of ground to make up with an inventory largely composed of older existing chassis during the COVID period.

Now with the post-COVID fall in marine chassis utilization, the price of chassis has fallen. According to sources, at the peak of demand, new chassis were going for over $23,000 and now $18,000 or less. But restocking in a down market isn’t a slam dunk as lower revenues for the IEPs accompany lower replacement costs. Still there is the belief that the current period will see a significant uptick in investment. Trac Intermodal in a May 2023 “Case study: Evolution of Chassis Pool Models” opined, “Despite import volumes trending lower in recent months, TRAC anticipates that 2023 will be a record year for equipment investment. This follows a record year in 2022, when fleet investment was up 130 percent over 2021 levels.”

While the explosive post-COVID freight surge was likely a once in a generation event, other supply shocks are inevitable. And it is still an open question of whether the chassis fleet is large enough to handle these wildly unpredictable movements in the supply and demand cycle.

A New Awareness of IEPs

What a difference a year makes… or more to the point, what a difference a plunge in international trade makes. Chassis utilization is down to about 50% and there is barely a murmur coming from disgruntled supply chain practitioners.

Nonetheless, while the kinks in the supply chain maybe straightened out [for now], there is still a lot going on in the chassis business. One thing that came out of the chassis boom associated with the enormous freight surge coming out of COVID is the awareness that the chassis is a critical piece of logistic infrastructure. The chassis will never quite get the play that trucking, and drivers got during COVID [no one holding signs along the roadside: ‘I love my chassis provider’]. In line with the high public profile the chassis business has garnered more attention from investors – particularly from the private equity sector, which have had an interest in the sector for years.

DCLI’s ownership journey more than any other epitomizes private equity interest in the chassis business. In 2022, GIC, OMERS Infrastructure, and Wren House have announced they inked an agreement to jointly acquire DCLI. They in turn bought DCLI from investment funds managed by Apollo and EQT. Apollo acquired DCLI from a private equity firm EQT Partners in 2018. And EQT in 2016 acquired DCLI from another private equity firm, LittleJohn & Co. DCLI’s chain of private equity involvement might be a little longer than most but is not unusual for the sector — and private equity might be heating up. In October, Consolidated Chassis Management (CCM) was bought by the fund managed by Oaktree Capital. CCM was formerly owned by Ocean Carrier Equipment Management Association, Inc. (OCEMA), an association composed of ten international container shipping companies.

IEP-Centric Business

OCEMA’s ownership of CCM was a natural extension of liner business. Mike Wilson, CEO of CCM in an AJOT article on the evolution of the chassis business and role of liner shipping, wrote, “This meant that chassis provisioning for the first 40-plus years of containerization up until the early 2000’s was ocean-carrier centric.” See The evolution of container chassis provisioning in the US

Around the same time as the 2008 financial crisis, ocean carriers began getting out of the chassis business and selling off their chassis assets, largely to chassis leasing companies — the IEPs.

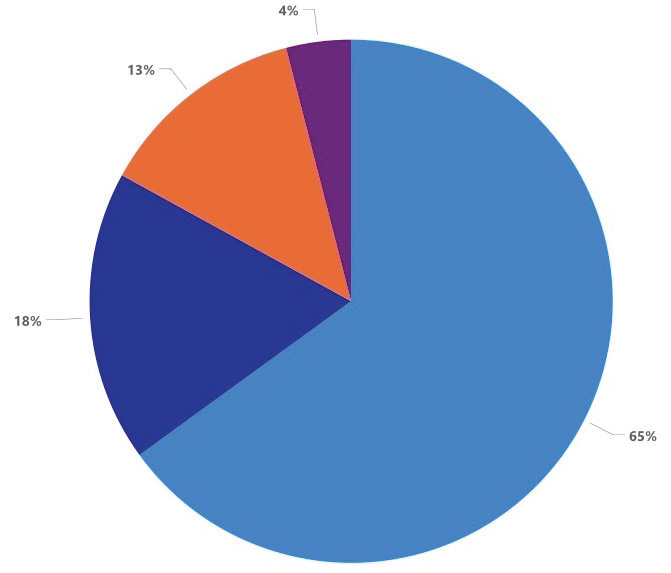

Not surprisingly the current composition of chassis ownership reflects the transition.

The Intermodal Association of North America (IANA) which is the main association for the IEPs regularly provides statistics on the business. In percentage terms ranks “Chassis Pools/Leasing Company” ownership at 65%, “Motor Carriers” at 18% and “Railroads” a 13% share and Ocean Carrier, which were once the largest now only at 4%. Considering that the container ship operators once owned nearly all the marine containers, the 15-year sell off represents a remarkable shift from a business “ocean-carrier centric” to now a “IEP-centric business”.

Pool Time

From a company perspective, there are a few big players operating in the marine chassis provisioning niche. In no particular order, DCLI, Trac Intermodal, Milestone, Flexivan, North American Chassis Pool Cooperation (NACP) and CCM are among the best known and largest. Virtually all the major IEPs participate in chassis pools which are designed to maximize equipment flexibility and efficiency. There is a confusingly large number of chassis pool models: Single Chassis Provider; Gray Pool – Independent Pool Manager; IEP Cooperative – Pool of Pools; Motor Carrier Pools; Private Pools; Port Pools; and some newer pool models like the SACP 3.0. [See page 11 George Lauriat “Is a New Chassis Business Model Emerging from the Launch of SACP 3.0?”] And new chassis pools are emerging to address specific demands. For example, in late October, FlexiVan announced its new FlexiVan Atlantic Chassis Pool (FACP), “offering a dedicated fleet of chassis at various locations for Ocean Network Express (North America) Inc. (ONE) customers,” with the operational area for located in Georgia and North Carolina.

As the TRAC Intermodal case study articulates, “The chassis pool sector is evolutionary, as the emergence of new pools with different ownership structures and management types indicates.”

How these various chassis provisioning models fare addressing the challenges of a post-COVID economy is as they say, a work in progress.