New empty container fee motivates carriers to evacuate excess boxes clogging port.

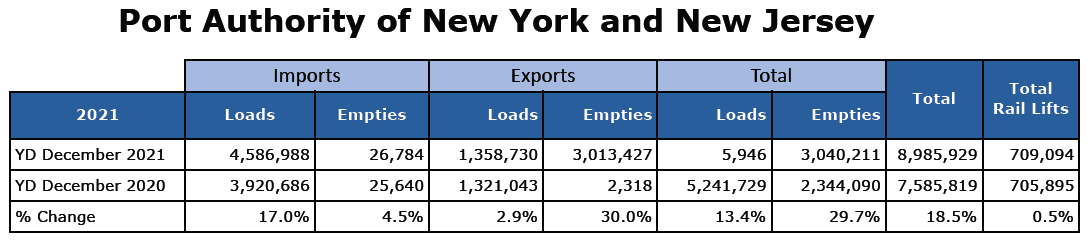

East Coast ports have been gaining cargo volumes at the expense of West Coast ports for nearly two years and the Port of New York and New Jersey have benefitted from that trend. The ports of Los Angeles, Long Beach, Oakland, and Tacoma all lost volume during the five months from April through August 2022 as compared to May through September 2021, according to figures supplied by Descartes Datamyne. New York/New Jersey, by contrast, was over 10% ahead of the pace set in 2021 during that period and saw an increase in volumes of 18.5% during the calendar year 2021.

Figures from the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey show that 70% of the cargo increases at the port this year, through July, have been cargo that has been diverted from West Coast ports. The question going forward is whether the trend is sustainable, or whether these cargo shifts represent tactical moves by shippers and carriers in the face of congestion and labor problems in the West.

The cargo increases haven’t been all good news for NY/NJ. The Descartes Datamyne figures show that between June and August of this year, the port saw increases in vessel wait times from 13.7 to 14.6 days, while Los Angeles and Long Beach, already with much shorter wait times, saw decreases during the same period. NY/NJ’s delays decreased to 13.6 days in September, but LA’s was down to 6.9 days and Long Beach’s down to 5.0.

East Meets West…Backlog

The port’s problems required some action that went beyond the coordination and collaboration afforded by the Council on Port Performance. (See Progress at the Port of NY/NJ: “Everything’s moving along.”) Since mid-February, the Port Authority and all of its terminal operators have been meeting on a weekly basis, under a discussion agreement authorized by the Federal Maritime Commission (FMC), to talk about capacity and fluidity.

“While we are a landlord port,” said Bethann Rooney, the new port commerce director, “it has become very important that we are not just collecting rent. We need to be cognizant of the entire supply chain, and all of the stakeholders that are working in and dependent upon the port.”

One of the issues that came to light during those discussions was the accumulation of empty containers at port facilities. “It’s a problem that became apparent during the first four or five months of this year,” said Rooney. “If we didn’t get on top of this, we were going to find ourselves in a position where we would have a lot more ships in the anchorage.” As of late August, 13 vessels were at anchor in waters near the port.

Unfortunately, talking alone did not motivate carriers to take action to rid the port of the excess of empty containers. They required some additional motivation, and that came in the form of a new empty container fee.

“The moment we put that structure in place,” said Rooney, “they became highly motivated. The carriers have been extraordinarily responsive and receptive to the idea of evacuating empty containers.”

Under the original container management scheme, announced on August 1, the ocean carriers’ total outgoing container volume, loaded and empty, would have had to equal or exceed 110% of their incoming container volume during the same period or be assessed $100 per container. The program has since been tweaked to tailor goals and fees to individual ocean carriers based on their historical imbalances.

“If a carrier falls short of its goal,” said Rooney, “a fee will be imposed, and then that shortage, plus the goal for the next quarter, get carried to the following period.”

Since the program calculates fees on a quarterly basis, no penalties will be imposed before January 2023, and proceeds will be used to offset the costs of providing additional storage capacity and other expenses incurred by the glut of empty containers. The Port Authority has repurposed 12 acres within Port Newark and the Elizabeth-Port Authority Marine Terminal for the temporary storage of empty and long-dwelling import containers and is looking for more space.

“By this time next year,” Rooney asserted, “75% of the accumulated containers should all be out in the port.”

Ocean carriers serving the port have developed some innovative plans for eliminating the backlog of empty containers. “We’ve seen an increase in the number of empty loaders, and we are seeing ships on certain voyages circling back to New York and making a second port call in order to evacuate empties,” said Rooney. “Some services that normally call New York first will call New York last in order to top off vessels with empties.” Several carriers, which don’t handle much export cargo out of the port, are chartering space on their vessels to carry empties on behalf of other carriers.

Rail Transportation Makes A Difference

Rooney has also noticed changes in the pattern of transporting containers, as many containers that headed to the Midwest by rail have not returned to NY/NJ as empties. “They just continue on to the West Coast where they are reloaded,” said Rooney.

When it comes to keeping the current volumes that have been diverted from the West, Rooney is confident in the capacity of the local terminals “because of the investments that the Port Authority and the terminal operators have made.”

“The challenge comes from the rest of the supply chain outside of the port,” she added. “It’s warehouse capacity, warehouse labor, trucks, drivers, chassis, rail cars, and rail labor. All of those components of the supply chain need to be right-sized in order to handle the volume that could potentially come this way and to handle it efficiently. If we can’t handle the volumes reliably, then it will go back to the West Coast.”

The last time the West Coast experienced labor concerns, the cargo was diverted east, and, according to Rooney, the Port of New York and New Jersey was able to retain a large portion of that cargo. “But we certainly were not struggling with the volumes back then that we have today,” she said.