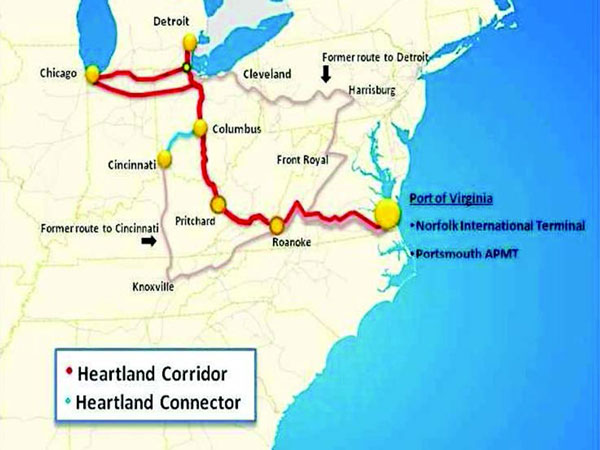

It’s almost exactly 11 years since the “Heartland Corridor” opened for business, providing an intermodal link from the Port of Norfolk, Virginia to, as the name implies, the U.S. Midwest “Heartland” with Chicago as the nominal end point.

In many respects the $391 million “Heartland Corridor” was an ambitious project that now with the Biden Administration’s Infrastructure Bill pending, might prove to be a blueprint – with caveats – for other future intermodal projects.

The Concept: U.S. 460

The Heartland Corridor is loosely delineated by U.S. 460 – a highway running east-to-west from Norfolk, Virginia to Frankfort, Kentucky and a spur of U.S. 60.

U.S. 460 travels a total of over 400 miles through Virginia, providing local access to a number of communities and connecting the larger areas of Lynchburg, Petersburg, and Hampton Roads. It also connects to U.S. 29 in Lynchburg, I- 81, I-95, and I-85. The Heartland Corridor is a key freight corridor.

It’s worth taking a look back at how the project evolved and what that might mean for other intermodal projects. The Heartland Corridor was a $397 million public-private partnership whose conceptual goal was to provide more efficient routing between the Port of Norfolk/Hampton Roads area and the U.S. Midwest.

Additionally, the project was built to provide added freight capacity and help relieve truck congestion on the interstates, improve double stack transit times, reduce greenhouse emissions and open up international trade.

Norfolk Southern freight rail lines run along most of the corridor as part of its Heartland Corridor, one of the important freight corridors in the eastern U.S, providing access between the Port of Virginia and the Midwest and into Chicago via Columbus, Ohio.

Conceptually, a double stack rail corridor would cut off nearly 200 miles of track from the then current route. It’s worth noting, while the Hampton Roads have long had rail connections, the original purpose was largely for the export of commodities like coal, agri-bulks and hi-cube double stack rail cars couldn’t effectively transit many of the rail routes thus forcing inefficient routing system, prior to the building of the Heartland Corridor.

However, to build an intermodal double stack system was going to require significant rail engineering to improve clearances, rail and road intersections and track capacity. For example, clearances were raised in 29 tunnels (any one of which was a major undertaking) to make way for double-stacked intermodal trains.

Financing the Corridor

The financing of the Heartland Corridor stood to be more complex than the engineering. The project would impact seven states, dozens of cities, numerous rail and road intersections and bridges, not to mention tunnels – the scope of the project would thus ensnare numerous state, federal and city agencies, along with the Norfolk Southern Railroad whose tracks comprise the Corridor. How to finance such a multifaceted project was simplified into a public-private partnership (PPP) largely between the Federal Government and Norfolk Southern.

At the heart of the effort was the actual “Heartland Central Corridor Double-Stack Clearance Project” which cost $191.6 million with a $6.1 million extension to Cincinnati. In addition, the Rickenbacker intermodal terminal in Columbus, Ohio added another $70 million. And the Commonwealth Railway serving the APM Terminal in Portsmouth, Virginia was relocated at a cost of $60 million. The Federal government granted $111 million for tunnel clearances and Rickenbacker intermodal terminal construction was from federal stimulus funds. The Commonwealth of Virginia provided another $9 million for tunnel clearances. Ohio Rail Development Commission (ORDC) contributed another $836,355 with Norfolk Southern picking up the rest of the tab. The U.S. Government funded $3.6 million for extension under the American Recovery & Reinvestment Act 2009 with the remaining $2.5 million provided by Norfolk Southern and the Ohio-Kentucky-Indiana Regional Councils.

Engineering the Corridor

A majority of the engineering challenge for the project lay on the main route. This section included 28 tunnels, seven railroad bridges, three overhead bridges, three railway signals and three sets of overhead wires. The project included increasing the vertical clearance of 28 tunnels and 24 overhead obstructions in the Appalachian Mountains by two feet above the head room to allow double-stack container freight trains. A majority of the tunnels were “round” shaped, as was common at the time of their original construction. These, round shaped tunnels were cut into square shape to increase the wall corners of the tunnel. Eight tunnels underwent linear notch work, 18 were replaced with new roofs and one daylighting tunnel was left as an open roof tunnel. Tunnels were also modified through roof excavation, liner replacement, arched roof notching, and track lowering and realignment. And it wasn’t just the height of the tunnels that needed to be addressed as the vertical clearance of the bridges at Ashville, Lubeck, Glen Jean and Ironton were also increased.

Legacy of the Heartland Corridor project

On September 9, 2010 the Heartland Corridor went into operation and eleven years later there is still debate on the “success” of the project. Certainly the project was an undoubted success in enabling an efficient (cutting 200 miles off the old route) double stack rail connection between the Port of Virginia (and specifically the APM Terminal in Portsmouth, VA) to Chicago and the Midwest.

Some have argued that Norfolk Southern didn’t contribute enough to the project (considering railroad was arguably the main beneficiary) and that some of the intermodal hubs (West Virginia) didn’t attract the freight that was anticipated in the proposed project.

Other arguments on the impact of the project are more circumspect. Did it really relieve truck traffic congestion on the highway? Did freight switch modes (truck to rail) because of the corridor?

While some studies suggest this was the case – some traffic did become intermodal freight – how much would have organically moved to multi-modal platforms is a more difficult question to answer. The project has also helped frame more esoteric questions, such as what is the minimum distance that an intermodal rail move makes sense? It’s easy to understand a Norfolk move to Chicago or Columbus but are shorter hauls worthwhile and at what cost?

Perhaps the biggest legacy of the project is that it works. That’s to say, it created more efficient access to the Midwest from an East Coast port. And within the context of moving goods throughout the continent over the next half century, intermodal is essential and the Heartland Corridor demonstrates that it works.