COVID-19 is still wreaking havoc with the supply chain but are there problems inherent with the system?

Making Sense of Chaos

It seems ever since the 20,000 TEU boxship Ever Given wedged itself across the Suez Canal, on March 23, 2021, the global supply chain has reeled from one disruptive event to another. The COVID-19 lockdowns are the obvious monkey-wrench in the supply chain but there are other snags, large and small, that have contributed to a dysfunctional system.

For everybody involved in the process, from the factory to the consumer, there is a yearning for normality that seems just out of reach.

But what is normal for the complex global supply chains that move our goods?

Just like the weather, there seems to be a climate change underway to the very eco-system of the global supply chain.

In 1972 MIT [Massachusetts Institute of Technology] Meteorology Professor Edward Lawrenz wrote a landmark paper entitled “Predictability: Does the Flap of a Butterfly’s Wings in Brazil Set Off a Tornado in Texas?”. The paper introduced the “butterfly effect” to illustrate how seemingly insignificant or unexpected events can cause unforeseen consequences – or chaos – far out of proportion to the initial action.

Like Lawrenz’s “butterfly effect,” large-scale supply chain disruptions are frequently the result of a culmination of smaller, often seemingly insignificant actions.

Take the Ever Given’s stranding. If the containership wasn’t hit by a crosswind at that very moment, or at that very place in the Suez Canal, or had the containership been 10,000 TEUs rather than 20,000 TEUs, or had the crew reacted better, would the chaos of a global $10 billion disruption to the supply chain ever happened? We’ll never know for certain but while there were many obvious issues – and a fair amount of post-accident finger-pointing – there were also many seemingly inconsequential events that contributed to the stranding.

And while the Ever Given stranding was a major disruption to the supply chain – carrying freight largely destined for Europe – from a big-picture perspective, it really wasn’t catastrophic. Within six-days the Suez Canal was cleared of obstruction and business returned to normal. In proportion to the global number of TEUs that passed through the supply chain in 2021, the damage was minuscule, albeit significant for containerized freight heading for Europe within the timeframe of the accident.

Notably, despite the incident, the Suez Canal traffic didn’t suffer a setback in 2021, as the waterway handled 20,649 ships compared to 18,830 ships recorded in 2019. And almost as a full-circle footnote to the year, on December 8th, 2021, a fully-loaded Ever Given transited the Canal to deliver Christmas cargo to Europe.

COVID: The Glitch That Ruined Christmas

COVID was in 2021, and potentially still is in 2022, a much bigger disruptor of the supply chain. And unlike the Ever Given incident, the pandemic can hit any link or even multiple segments in the supply chain from manufacturer to consumer with ever-widening impacts. Further, only a small incident can expand exponentially through the entire supply chain. Take the Meishan Terminal event in late last summer. The PRC (Peoples Republic of China), enforcing the ‘zero-COVID’ strategy, shut down the Meishan Terminal at the port of Ningbo-Zhoushan in August 2021 after one port worker tested positive. The terminal remained closed for nearly two weeks in contrast to the six days the Ever Given obstructed the Suez Canal. The Port Ningbo-Zhoushan throughput in 2020 was nearly 29 million TEUs, ranking number three in the world behind Shanghai and Singapore. (See AJOT Issue 727, page 26, “AJOT’s 5 Million TEU Club” chart).

By itself, the Meishan Terminal’s annual throughput is just over 7 million TEUs, or by way of comparison, roughly the same as the entire throughput of the Port of New York/New Jersey (at 7.59 million TEUs). For that reason, it’s not surprising that with the closure of a mega-terminal like Meishan that containerships were piled up at other Chinese ports and that the entire supply chain slowed to a crawl, resulting in innumerable delays for consumer merchandise scheduled for holiday delivery.

A recent blog posted by Rotterdam-based Shypple, a company that operates an online shipping platform, illustrates the widening impact of a Meishan-like shutdown on deliveries: “After the major lockdown in Ningbo [Ningbo-Zhoushan] in August, experts estimated that it would take up to 60 days for normal port operations to resume…it is currently recommended that retailers plan at least 70 days further in advance [Editor’s Italics], compared to normal shipping schedules.” Shypple also added, “the average delay per container used to be roughly half a day in January 2019. By the end of 2021, it was more than a week.”

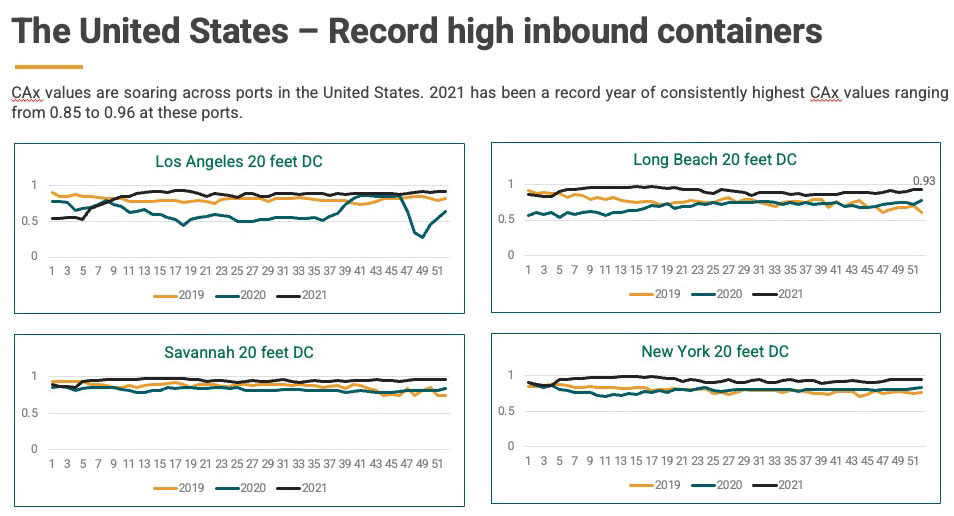

Lars Jensen, a well-known containership trade analyst at Copenhagen-based Vespucci Maritime Consulting, noted that during 2021, Trans-Pacific ocean carrier transit times went from 45 days to 110 days. The result was that at the Ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach there have been over 100 vessels waiting to unload at container terminals and even now there have been only slight decreases. (See Jensen warns Russia-Ukraine conflict might generate cyberattacks on ports)

And while the launching of vaccines has begun to stem the tide of COVID-19, as shipbrokers SSY (Simpson Spence & Young) wrote in their 2022 Outlook, “the Omicron variant of Covid-19 emerged towards the end of 2021, (is) proving a challenge for governments to control. This may create a lag leading from the end of the year into 1H22 [1st half of 2022] for logistics and international trade…”

The downstream impact of the Chinese port delays was shortages compounded by the urgency of consumers to buy and retailers to restock before the holidays.

Uber Freight in their “Market Insights Report for 2022”, remarked: “In December, manufacturing expanded for the 19th month in a row since the beginning of the pandemic. Despite these signs of growth, inventories still did not increase enough to satisfy demand and maintain pre-pandemic inventory-to-sales ratios. Retailers warned shoppers to buy their holiday gifts earlier than usual and spending surged at a faster rate than inventories, forcing retailers to pay more just to fill their shelves. Many imported goods were stuck at ports, further raising retailers’ willingness to pay to get their gifts out before the holidays - the sunk cost of international shipping and importing was already higher than any inflated trucking rates.”

There was also an ancillary effect, still being felt, that was brought on by the uncertainties of consumer demand.

In an article in the Council on Foreign Relations, entitled “What Happened to Supply Chains in 2021?”, Anshu Siripurapu, wrote: “Despite their efficiency, supply chains have long proven difficult to manage. Because each point in the chain receives limited information about a product, small changes in perceived consumer demand at one end can cause big changes in production at the other—a phenomenon known as the bullwhip effect.”

As Siripurapu explained, a retail store, seeing a spike in weekly purchases of a particular item, ups its order from a wholesaler, which in turn orders even more from the manufacturer – setting off a demand cycle that can be out of sync with the delivery cycle of the supply chain.

Rebalancing the Machine?

Part of the problem with the supply chain is that it is weighted heavily on the inbound side from Asia, particularly China. The machine is inherently out of kilter. This imbalance means that the supply chain is really designed around the leg from Asia rather than as a balanced mechanism. (See US trade figures) The situation is further aggravated by the nature of the trade – the export raw materials are of lower value and have a much less complex supply chain than the consumer manufactured goods coming in on the inbound side.

Thus, it is natural a preponderous of the world’s largest ports and terminals lie in China and Southeast Asia rather than other regions.

As one port executive said of the situation, “their [Asian-based terminals] berth throughput is just so much higher than ours…and that is what happened in August, they just have outproduced…it’s just a much bigger machine.”

And the machine is getting bigger. The ships are bigger, now hitting 20,000 plus TEUs. Even the all-water Trans-Pacific schedules to the U.S. East Coast are served by 12,000-14,000 TEU vessels. In 2021 it is estimated that 827 million TEUs were shuttled through global supply chains, up over the 775 million TEUs handled in 2020. It is forecast that this total rises to 945 million TEUs by 2024 – only two years away.

But the supply chain is designed to be a lean machine. The concept of a “Just-in-Time” supply chain with the emphasis on velocity is not equipped to handle disruptions as very little redundancy is built into the system. The imbalance in the trade leads to inventory problems, even when the supply chain is working well.

There are well-documented regulatory efforts afoot in the U.S. and other countries to ensure the “supply chain” functions along more equitable lines. Whether these legislative efforts help is difficult to say, as economics like water tends to seek its own level.

McKinsey & Company in a recent study entitled “How COVID 19 is reshaping Supply Chains” observed of the imbalance issue: “It’s quicker to build inventories than factories.” They could have added that is also easier to build or buy warehousing (and currently there is a massive run of purchasing warehouse space in the U.S.) than to worry about velocity. There is also a shift towards alternative sourcing underway towards Southeast Asian nations like Vietnam and Indonesia and other regions like Latin America, away from China. There is also a new impetus to reshore or nearshore critical industries (like semiconductor production) back to the U.S. And certainly, the emphasis on digitalization and visibility in the supply chain is also part of the retooling to handle an increasingly complex supply chain.

With or without COVID’s importune impacts, the question is how well will all these solutions work with a flood of 945 million TEUs just around the corner?