Nogales is a “Tough nut to crack” for imported Mexican produce

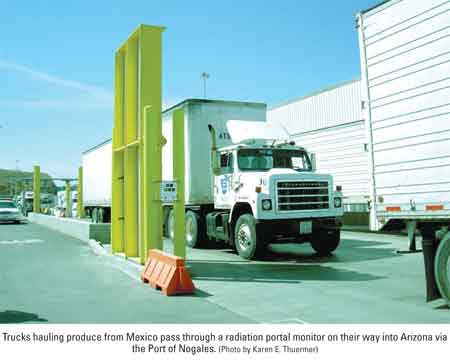

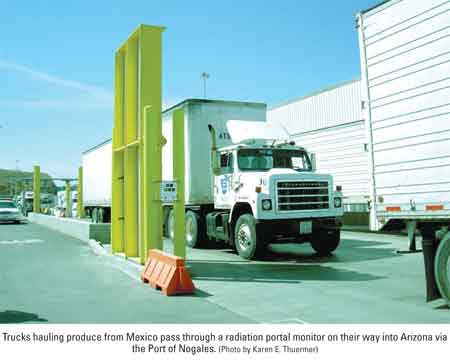

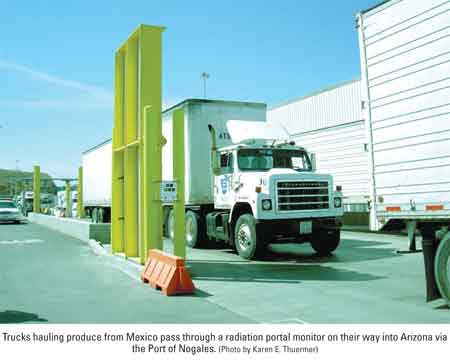

By Karen E. Thuermer, AJOTNogales means “walnuts” in Spanish, but to growers, shippers and importers it conjures up images of melons, tomatoes, citrus, peppers, squash and gourds, beans, grains, corn, tropical fruits, avocados, and even grapes and apples. That’s because Nogales is the largest port of entry for agricultural products from Mexico into the United States. Some 1,300 trucks pass through the Arizona port daily. Nearly 1,000 of them haul produce.

“Depending on the year, nearly 60% of Mexico’s seasonal fruits and vegetables—over 120 different commodities, are imported through Nogales,” states Manuel Trujillo, Jr., chief of Agriculture Operations, US Department of Homeland Security (DHS), Nogales, AZ.

Included are half of Mexico’s exported mangoes and one-third of its avocados. The produce comes primarily from the Mexican states of Sinaloa and the Senora.