Egypt pushed ahead with an increase in transit fees through the Suez Canal this week, as a need for foreign currency trumped a fall in maritime traffic due to Houthi attacks on shipping in the Red Sea.

Revenue for the North African nation from the vital waterway — the shortest route between Asia and Europe — has slumped as some ships avoid the canal to protect themselves from missile and drone assaults. But rather than delay the long-planned hike, Cairo is betting additional income from those still transiting will help the cash-strapped economy.

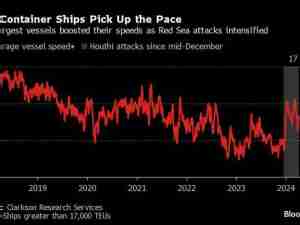

Traffic volumes through the Suez Canal were down 30% between Jan. 1 and Jan. 11 compared with a year earlier, according to canal authority head Osama Rabie, as the Iran-backed Houthis stepped up their attacks in response to Israel’s war against Hamas in Gaza, fueling concerns of a wider military conflict.

“Because of security concerns, commercial ships may prefer longer routes than entering a war zone,” Rabie told a talkshow on the MBC Masr TV channel late last week. “Even if I decreased tariffs, it won’t have an impact, because these are security fears.”

Egypt, which increased the fees Monday, had also been working on expanding the waterway to bring in more revenue from what’s one of its prize assets. The Middle East’s most populous country is in talks with the International Monetary Fund over the possibility of at least doubling its current $3 billion rescue package.

Attacks by the Houthis on vessels passing through the Red Sea have added to pressures, with the Yemen-based group’s leaders vowing to step up its assaults even after the US and allies began airstrikes to deter them. The Houthis said they were only targeting ships linked to Israel in response to the war in Gaza, but now say the US, UK and others are fair game.

A.P. Moller - Maersk A/S and Hapag-Lloyd AG are among firms to have diverted ships, with some being rerouted around the tip of Africa — a far longer and costlier journey.

The Suez Canal Authority raised transit fees by as much as 15% for some tankers, including those carrying crude oil and petroleum products, according to the October circular. Shipping company security concerns won’t be overcome with discounts or other incentives offered by the canal, Rabie said.

“The impact of the crisis on global navigation is big, slowing down supply chains,” Rabie said. “It reminds us of Covid. Ships are not moving and if they do they arrive late.”

Annual revenue from the canal reached $10.25 billion in 2023, Rabie said, and if the situation continues, the figure will be “very affected” in the current year. That said, many ships are still going through the canal.

Egypt — which almost never stages military actions outside its borders — has made clear it fears any regional escalation that may have even graver implications for stability. That means the most Cairo is likely to do is keep pushing for a permanent cease-fire in Gaza, while resisting any effort to allow Palestinians to migrate en masse across the shared border.

“Egypt can cope with a few weeks of lower traffic through the Suez Canal,” said Riccardo Fabiani, project director for North Africa at the Brussels-based Crisis Group. “But it cannot live with the permanent displacement of Palestinians into the Sinai Peninsula and the Gaza war’s crippling economic effects and risks of regional war.”