Nafta Can Be Reworked Without Hurting Earnings

By: Komal Sri-Kumar | Jul 27 2017 at 05:00 AM | International Trade

There is understandably some nervousness in Mexico before talks next month to reset the terms of the 23-year-old North American Free Trade Agreement.

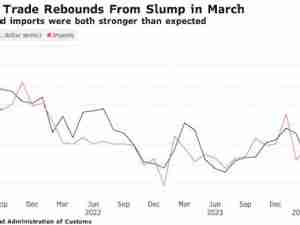

Nafta has provided the underpinning of Mexico’s prosperity over the past two decades, and any radical change could cause global investors to rethink investment plans for the country. According to the Census Bureau, the U.S. ran a $63.2 billion merchandise trade deficit with its southern neighbor in 2016, a 4.2 percent increase over 2015 (chart below).

The imposition of restrictions on trade by the U.S. would almost certainly invite retaliation by trade partners, slow the pace of Mexican, American and global growth, and puncture the equity bubble.

Yet at the same time, a potential reduction in the U.S. trade deficit may not be incompatible with speeding the rate of economic growth and could have a positive impact on corporate earnings. There are two ways this could occur. The first came in a proposal from Ildefonso Guajardo, Mexico’s minister of the economy, in a Wall Street Journal interview on July 22.

Guajardo seeks a path to increase the overall level of trade as part of Nafta discussions rather than focus on a reduction of imports from Mexico. He pointed to the opening of the Mexican energy sector to foreign direct investment during the current administration of President Enrique Peña Nieto, and suggested that this meant that foreign oil companies investing in Mexico would need additional imports of machinery and equipment. A large portion of these purchases is likely to be made in the U.S., reducing the U.S. trade deficit. Top U.S. exports to Mexico in 2016 were electrical and other machinery, vehicles, mineral fuels and plastics—all of importance to the energy industry. Sales of these items amounted to $140 billion (or 60 percent) of the $231 billion total exports.

The second way that the U.S. can reduce its deficit is by requiring companies and contractors to be allowed to compete for opportunities in Mexico’s energy sector. In addition to increasing Mexican demand for U.S. products, successful investments are likely to increase inflows to the U.S. from dividend payments and capital appreciation. A greater opening of Mexico to foreign investors would be positive for financial markets on both sides of the border.

To investors, how the U.S. payments deficit would be reduced is crucially important. Narrowing the shortfall through combative tit-for-tat measures would weaken the peso and cause a drop in Mexican equity prices. An estimated 40 percent of the content of Mexican exports to the U.S. is U.S.-made, and a reduction in Mexican exports would hurt U.S. employment and could even end up increasing the U.S. trade deficit.

Furthermore, Mexico is the top export destination for California and Texas, and any new tariff measures could be expensive for the U.S. in other ways. For example, computer and electronic products, transportation equipment, and machinery are top California exports to Mexico, and Silicon Valley companies would feel the hit on earnings and share prices if a trade war develops.

On the other hand, if U.S. negotiators succeed in obtaining greater opportunities for investments south of the border, it would be a win-win for both the U.S. economy and for companies making the investments. Such a benign process for reducing the U.S. payments deficit would enable the Trump administration to keep a key campaign promise in a market-friendly manner.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.