Russia’s growing trade with China has helped its economy withstand Western sanctions. Now Moscow is preparing to spend billions to upgrade its vast eastern railroads to speed up the burgeoning cooperation.

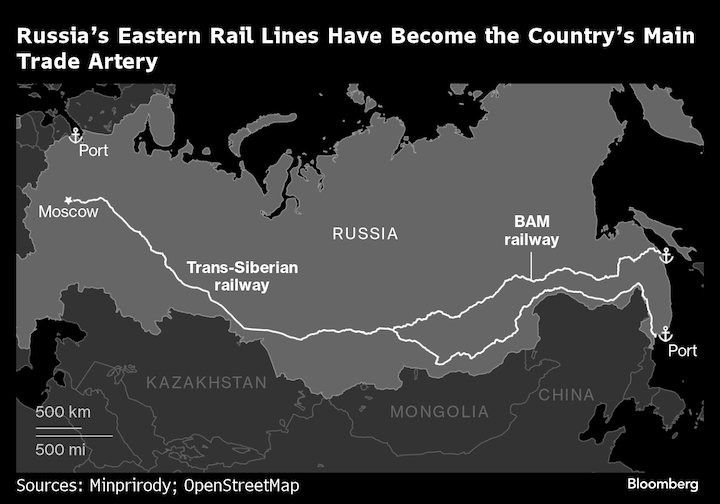

Vladimir Putin outlined plans to boost annual shipping capacity on Russia’s two longest railroads, the Trans-Siberian and Baikal-Amur Mainline, to 210 million tons by 2030, in an address to the Federal Assembly on Feb. 29 ahead of next week’s presidential election. The rail lines handled about 150.5 million tons of goods in 2023, according to the Kommersant newspaper.

The 8,700 miles of railway tracks, also known as the Eastern Polygon, constitute a vital artery for Russia’s foreign trade, linking its western regions with the Pacific Ocean and China. Yet the routes have long been beset by logistical issues and currently operate below their nominal capacity, despite booming trade with Asia. The railroads in 2023 handled about 13% fewer goods than their stated capacity, Kommersant reported Feb. 28, citing documents from the Transportation Ministry.

That underscores the infrastructure challenges Russia faces as it continues to reorient its economy toward Asia and away from Europe in the wake of sanctions over Putin’s invasion of Ukraine.

Given the growing cooperation between China and Russia, “the importance of developing the Eastern Polygon continues to increase,” said Anastasia Pyatachkova, a lecturer at the National Research University Higher School of Economics. “Rail transportation remains one of the most convenient ways to transport certain types of cargo, including coal.”

Even before Putin sent troops into Ukraine, domestic shippers faced impediments on the route as they moved goods and commodities such as coal to Asia. Infrastructure shortcomings, delays in loading and trade imbalances all contribute to bottlenecks that limit how much is shipped. The war also has exacerbated traffic along the links, with the military using them to move tanks and missiles, while the increase in trade between Russia and China after European sanctions has stoked demand.

In the past, Russia “‘yawned’ a little, didn’t do something on time,” Putin said during his address. “Now we have to catch up, and we will make up for it.”

Russia has already spent billions of dollars to nearly double the capacity of the rail lines to an expected 180 million tons this year from 97.8 million tons in 2013. Yet, current demand is twice as high as the track can handle, state-run Rossiyskaya Gazeta said in February, citing government data.

This year alone, Russia plans to spend 366 billion rubles ($4 billion) to improve the Eastern Polygon’s infrastructure. Details of the additional investments Putin announced are expected to be approved in March, Deputy Transportation Minister Valentin Ivanov told reporters last month, according to the Tass news service. That work may continue through 2032 and require 2.7 trillion rubles of investments to increase the capacity of the rail lines to an eventual 255 million tons per year, according to Ivanov.

Demand for shipping on the Eastern Polygon is forecast to be 552.5 million tons by that time, Pyatachkova said.

Most of the current issues aren’t new — they have existed for years, several people from the biggest commodities groups that use the railways said, declining to be identified as the information is sensitive. It’s not only insufficient infrastructure, but also what gets shipped that’s creating the bottlenecks.

Trains carry coal and other commodities to the east, while bringing consumer goods westward. Those shipments require different types of rail cars and containers, which increases the wait times on both ends for loading, the people said. The same track is also used for domestic shipping and by passenger trains, adding to the traffic.

Trade between Russia and China reached a record $240 billion in 2023. Russia’s eastern neighbor has become the supplier of everything from clothes to machinery and cars after an exodus of western manufacturers in the wake of the invasion. At the same time, Russia has boosted exports of commodities such as coal and aluminum to China as Europe shuns Russian metals and mining companies even when they are not sanctioned.

Separately, investment in a plan to build two new rail links to China by 2030 is expected to be discussed this and next year, according to a government strategy for Siberia’s development. As of now the countries, which share 2,615 miles (4,208 kilometers) of common border, have only four railway border crossings.

What Bloomberg Economics says...

Railroad investment is in line with Russia’s ultimate goal to see China fully replace Europe in terms of energy trade, technology transfer and financial markets. Today, the capacity of the Trans-Siberian and Soviet Baikal-Amur Mainline is stretched to its limits, so their expansion will enable Russia to boost its trade with China. In the medium term, there are three risks that this project will face - sanctions, energy transition and funding.

Alex Isakov, Russia economist

Still, there are signs that the Chinese economy is slowing down, said Alexander Gabuev, director of the Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center. That would give Russia time to expand its infrastructure. If the International Energy Agency’s forecast proves accurate, China’s demand for coal may peak in 2025 and start to fade in the coming years, which may result in new railroad capacity being underutilized, Alex Isakov of Bloomberg Economics said.

After the West imposed limitations on Russian oil shipments, some companies resumed moving the commodity by rail, adding to the demand. The Energy Ministry is seeking priority for moving oil and oil products by railroad, similar to what coal exports enjoy, after some refineries complained that Russian Railways wasn’t accepting the commodity for shipments, RBC news site reported this month.

Russian Railways didn’t respond to a request for comment.

The route is key for trade throughout the region, and bottlenecks along the line can even affect Russia’s neighbors. Polymetal International Plc’s Kazakh unit has faced delayed gold concentrate shipments to clients. Some of that metal is exported to China on Russian Railways, which has experienced capacity issues, the company’s executives said in January.

Where it is possible, goods are often re-loaded onto lorries in Siberia and then trucked to China, some of the people said.