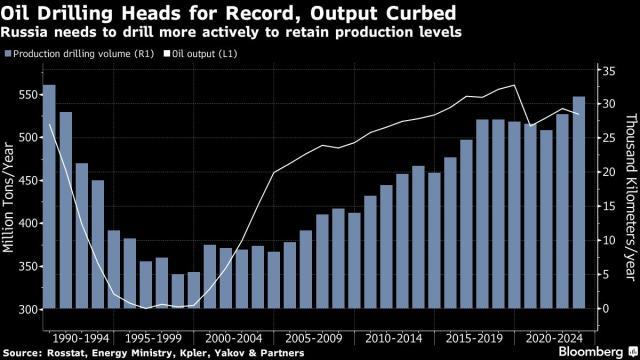

Russia was on pace for a second year of record oil drilling in 2023, further evidence of the nation’s resilience to Western sanctions.

The boom in activity came alongside a recovery in both the volume and value of Russia’s oil exports, a stark illustration of how the country’s fossil fuel industry has been a crucial source of funds for President Vladimir Putin’s war in Ukraine, which is about to enter its third year.

“Russia is substantially more independent in its oil-field services than generally appreciated,” said Ronald Smith, an oil and gas analyst at Moscow-based BCS Global Markets.

In the first 11 months of 2023, Russia drilled oil production wells with a total depth of 28,100 kilometers, according to industry data seen by Bloomberg. That’s on track to beat the previous year’s post-Soviet record.

The frenetic pace of drilling — amid fairly static production — also offers an indication of some long-term problems that may be building up for Russia’s oil sector as a result of Moscow’s international isolation. The industry is working harder to maintain output from its oldest wells, while new projects that would sustain production in the coming decades must adapt to the country’s changed circumstances.

For 2023 as a whole, Russia’s production drilling is set to top 30,000 kilometers, according to analysts at intelligence firm Kpler and Moscow-based consultant Yakov & Partners. The increase comes despite Western countries’ pressure on the country’s energy industry, which is a key source of funds for the Kremlin’s war in Ukraine. The sector has been the target of sanctions ranging from import bans and price caps, to prohibitions on the export of technology.

Last year, the US sanctioned dozens of companies that produce drilling equipment and develop new production techniques, aiming “to limit Russia’s future extractive capabilities.” The European Union in 2022 imposed “comprehensive exports restriction on equipment, technology and services for the energy industry in Russia.”

Two of the world’s largest oil-service providers — Halliburton Co. and Baker Hughes Co. — sold their Russian units and withdrew. Two more giants, SLB and Weatherford International Plc, have said they continue operations in the country in compliance with sanctions.

Failed Goal

The data indicate that these restrictive measures have largely failed.

“Only some 15% of the nation’s domestic drilling market depends on technologies from so-called unfriendly nations,” said Daria Melnik, vice-president for exploration and production at Oslo-based research firm Rystad Energy A/S.

The withdrawal of major Western oil-service companies from Russia had minimal impact because it largely left intact their local subsidiaries. These operations “were mostly sold to management, retaining the know-how built up over the years,” said Viktor Katona, lead crude analyst at Kpler.

Russia’s exploration drilling rates have also resumed growth after dipping in the wake of the pandemic, industry data show, although they remain below the 2019 peak.

“In crisis times, when companies have to optimize their investment budgets, high-risk projects, including exploration, are slashed,” Rystad Energy’s Melnik said.

Still, for the full-year 2023, Russia is set to drill exploration oil wells with a total depth of just over 1,000 kilometers, according to Dmitry Kasatkin, a partner at Kasatkin Consulting, formerly Deloitte’s research center in the region.

The drilling boom is a sign of Russia’s resilience to Western energy sanctions, but the pace of activity also carries a warning.

Over the years, the rise and fall of the nation’s drilling has moved largely in sync with changes in output, historic data show. Yet in 2023, the drilling boom came alongside production cuts that Moscow is implementing in tandem with the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries. That suggests the high level of activity is necessary simply to maintain output.

“The main reason for the growth in Russia’s drilling is the need to launch new wells,” said Gennadii Masakov, director of the research and insights center at Yakov & Partners. “New wells have to be launched as the currently producing fields are depleting.”

As of 2022, fields that had been in operation for more than five years accounted for nearly 96% of Russia’s total liquids production, according to a research paper from the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies. Many of those upstream projects are long past their peak output levels, the paper said.

“Natural decline is a routine factor” for the nation’s industry, said Sergey Vakulenko, an industry veteran who spent ten years of his 25-years career as an executive at a Russian oil producer.

Depletion has to be compensated either by new drilling at existing sites, so-called brownfields, or by new projects known as greenfields. The latter could be problematic, said Vakulenkо, who is now a scholar at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace in Berlin.

“Pre-war planned greenfield developments were conceived with Western technologies in mind and need to go back to the drawing board to be adjusted to the available technologies,” he said. “In the meantime, Russian oil companies are trying to maintain the plateau by accelerating production in the brownfields.”

Some components from foreign suppliers are difficult to obtain and “the Russian industry might have to resort to simpler wells and fewer frack stages as a result of missing parts,” Vakulenko said. “This would make the wells less productive and more expensive per barrel of oil produced.”

The technological independence achieved by its drillers will be enough for Russia to keep output stable in the medium-term, said Yakov & Partners’ Masakov. Yet over time, the efficiency of Russia’s drilling operations will decline, potentially risking as much as 20% of the nation’s output if untapped reserves become uneconomic to develop, he estimated.