The US is betting the transition to cleaner energy combined with massive infrastructure investments will reverse a persistent decline in family farms, creating new revenue opportunities for growers while boosting their ability to compete overseas.

More than half a million farms across America’s landscape have vanished over the last four decades as policies favored consolidation. While the resulting industrial heft has bolstered the US’s status as an agriculture juggernaut feeding the world, it’s wreaked havoc on smaller and mid-sized producers and the rural economies that rely on them.

But a revival is under way, according to US Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack. “We have to change the direction, otherwise in 40 years we will be saying we lost another 500 million acres,” he said in an interview Tuesday at Bloomberg’s Chicago office.

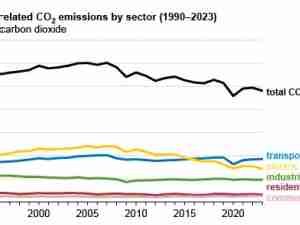

His agency is devoting tens of billions of dollars to promote climate-friendly farm practices as the world races to decarbonize, dealing with everything from fertilizers to grazing methods. The aim is to lower the greenhouse gas emissions of farming, and making growers eligible to take part in potentially lucrative new markets like crop-based sustainable aviation fuel.

Initiatives include enabling farms to profit by monetizing their excess renewable electricity, as well as helping them tap into new markets to sell into, including schools and farmer markets. The USDA also is devoting funds to create more robust export opportunities for US producers in regions such as Africa, Southeast Asia and Latin America.

“This is allowing farmers to say to the next generation: ‘You can be entrepreneurial and make a difference in the world,’” he said.

The opportunity to profit from selling more into local and regional food systems is significant. While farmers may get around 15-21 cents of a dollar spent at the grocery store, they can get as much as 75 cents at a farmers market or other venues in which growers work directly with consumers, Vilsack said.

Yet uncertainty is hanging over whether US farmers can shrink their carbon footprint fast enough to be competitive with grains and oilseeds from other nations, as well as with other pathways for making high-value products like sustainable aviation fuel, or SAF.

In January, the world’s first plant using ethanol of all types to make SAF was unveiled in Georgia. A thousand miles north in Iowa, the country’s biggest producer of corn-based ethanol, farmers and biofuel makers said the opening was a wake-up call to move faster to decarbonize to compete with ethanol from Brazil.

Vilsack, a former Democratic governor of Iowa, predicts a “rapid acceleration” in crop-based SAF investment after the Biden administration releases long-awaited details on federal tax credits aimed at setting off a surge in American production of lower-emitting airplane fuel. The update of a US tool used to calculate greenhouse gases from the transportation and energy industries is expected within a few weeks, Vilsack said.

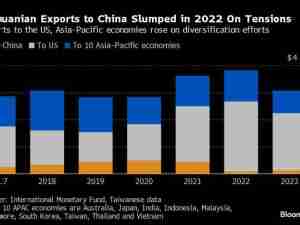

While the government’s strategy is focused on strengthening the small farmer and rural communities, Vilsack expects the administration’s policies to also bolster the US’s position in world markets. America over the past decade lost its status as the top global shipper of corn and soybeans to Brazil.

Once the US fixes its roads and bridges, and the rail and port systems work more efficiently, America will be able to reclaim its infrastructure advantage, he said. President Joe Biden’s $1 trillion infrastructure law, passed in 2021, will “change the game on exports,” Vilsack said.

While he declined to comment directly on this year’s elections, Vilsack said he sees little risk in a new administration coming in and possibly rolling back efforts to help rural America, as the shift toward clean energy will be hard to stop.

He said farmers 10 years ago would have said “no thank you” to climate-smart programs, but now farm groups and growers are increasingly understanding the benefits.

Changing Mindset

“It’s an unlimited entrepreneurial opportunity to get out of the ‘Get Big or Get Out’ mindset,” he said. The phrase is a reference to the mantra of Earl Butz, agriculture chief under presidents Richard Nixon and Gerald Ford, which was also taken up by President Donald Trump’s farm chief Sonny Perdue.

“Now the rest can get entrepreneurial,” Vilsack said. “They can have two or three income streams and may not have to work that second job.”

Vilsack, who also served as agriculture chief under Barack Obama and is the second-longest serving USDA secretary in US history, said his approach is not about taking on crop-handling behemoths like Cargill Inc. and Archer-Daniels-Midland Co.

“This is about saying we ought to be able to create more options, and then the farmer can make the decision about what is best for his or her operation,” he said. “That’s the beauty of this — it complements, it doesn’t compete.”

_-_28de80_-_939128c573a41e7660e286f3686f2a6e25686350_yes.jpg)