As US debt ceiling talks continue without resolution, the threat to domestic manufacturing ramps up.

The ongoing US debt ceiling negotiations are threatening the ability of the country’s low-carbon supply chain to catch up with foreign peers.

The Inflation Reduction Act is expected to increase supply chain capacity and domestic renewable demand, reduce US solar PV project costs and aid the expansion of battery cell output, while also incentivizing expansion of domestic low-carbon manufacturing.

Permitting reform complexities aside, if the debt ceiling negotiations undercut the Act’s low-carbon supply chain incentives, the global competitiveness of US manufacturing will take a significant hit.

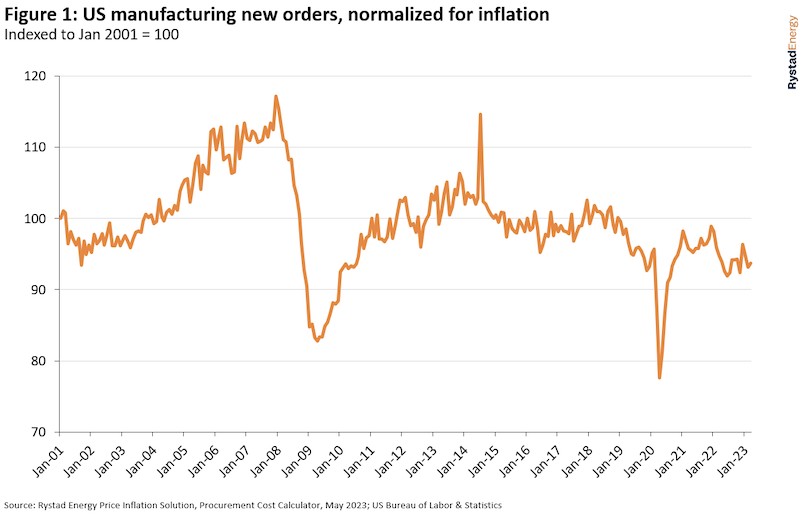

US manufacturing is at almost its lowest inflation-adjusted level for the past 20 years.

Only the immediate aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis and the Covid-19 pandemic-impacted year of 2020 saw such low inflation-adjusted manufacturing activity.

While manufacturers’ new orders are at an all-time high in absolute terms, this is due mainly to the prolonged inflationary period rather than a result of a booming industry.

The Inflation Reduction Act was poised to give a much-needed boost to what was a stagnant domestic manufacturing industry.

In November last year, TPI Composites announced a comeback in its recently closed Newton facility in 2024 by signing a 10-year lease extension with General Electric Renewable Energy, a comeback it partly credited to the new legislation.

The beginning of this year has also brought fruits, with GE announcing proposals of constructing two new offshore wind facilities (one blade facility and one nacelle facility) in New York, Siemens Gamesa with ambitions of constructing an offshore wind turbine nacelle facility in New York (in addition to its Virginia offshore wind blade facility construction, announced back in 2021).

Orders of US-made oil and gas field machinery hit record highs from 2010 to 2014, sustaining new monthly orders of near $3 billion.

Since 2016, orders have yet to eclipse $2 billion for any month.

Adjusting for inflation, the picture looks even bleaker: new orders in this year’s first quarter are almost one-third below the average between 2010 and 2014.

In absolute US dollar terms, new orders in the first quarter of this year were over $1.7 billion per month – the highest since the second quarter of 2015.

When adjusted for inflation, however, they are below new orders in the first quarter of 2020 before the onset of the pandemic late in that quarter.

Similarly, contractionary or stale trends have also been observed when normalizing new manufacturing orders in the US for industrial machinery, electrical equipment and power transmission equipment, such as turbines and generators – none have boasted substantial inflation-normalized growth since the early 2000s.

While technological advancements have helped, they have not offset rising labor costs.

US manufacturing activity is also heavily influenced by the strength or weakness of the US dollar relative to other currencies.

As the US dollar strengthens, goods manufactured outside the US become more cost competitive.

Between 2002 to 2007, the weak dollar was a major contributing factor to the surge in domestic manufacturing activity.

Over the past two years, the dollar has been abnormally strong, triggering a significant cost disadvantage for US manufacturing against international orders.

The global low-carbon manufacturing opportunity set is both significant and growing rapidly.

While the US is well positioned for domestic wind equipment manufacturing, that work has required a heavy reliance on foreign manufacturing imports.

The domestic supply chain was going to leverage the credits from the Inflation Reduction Act to better compete for international orders.

Investments in 2023 will grow year-on-year by over 25% for onshore and offshore wind, as well as 138% for hydrogen and 494% for carbon capture and storage (CCS).

All told, global investments in renewables are on track to be larger than those within oil and gas by 2025.

Without the supply chain boosting credits from the Inflation Reduction Act, the US low-carbon manufacturing sector will be at a significant disadvantage when competing globally.

If the US fails to capitalize on the opportunity, original equipment manufacturers in mainland China will swoop in and take an even larger slice of the global offshore wind sector.

With wind sector spending expected to increase by $70 billion in 2023, China looks primed to maintain its firm grip of global wind manufacturing market share.

This is in addition to the country’s solar supply chain dominance, with cost-competitive solar PV module fabrication.

Global manufacturing powerhouses like China remain hungry for international orders to boost struggling activity levels.

If the Inflation Reduction Act’s tax incentives are removed, the US will struggle to compete on a global scale.

Considering the state of the US manufacturing industry at large, this potential repeal would be yet another setback to the domestic manufacturing industry and would see the country’s manufacturing sector miss out on the rising tide of global low-carbon demand.