Beijing’s assault on US agricultural exports is blatantly designed to get the Trump Administration’s attention.

Tit for Tat. In early April, the USTR (United States Trade Representative) released a list of $50 billion worth of Chinese electronics, machinery and aerospace products for a recommended 25% import tariff. On April 2nd, immediately after the US steel and aluminum tariffs went into effect, China responded with tariffs on imports of 128 US product lines. Out of the total 128 products, 94 targeted agricultural products with the remainder steel and aluminum (see Peter Buxbaum and Manik Mehta articles on pages 6 & 7). The agricultural commodities fall into two sectors: 86 products, including fresh and dried fruit, tree nuts and wine, that are subject to an additional 15% tariff and eight products, including pork, that are subject to an additional 25% tariff. Collectively, these tariffs impact an estimated $2 billion worth of U.S. food and agricultural exports.

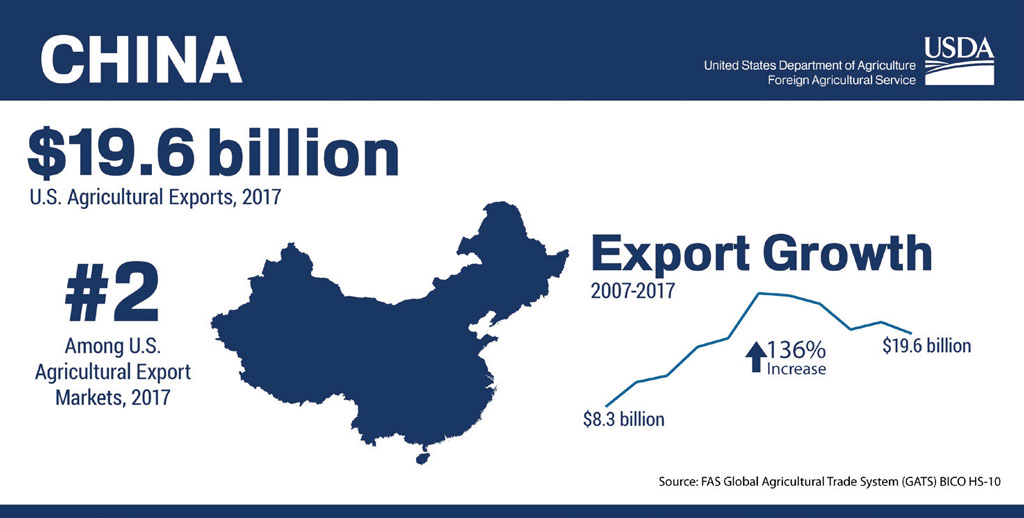

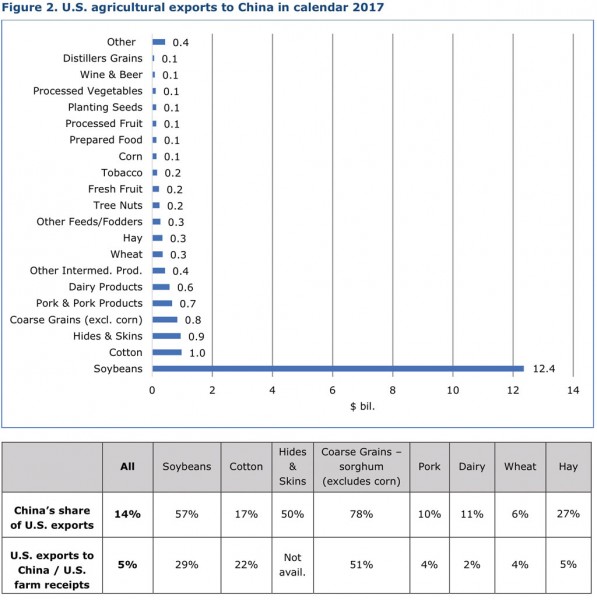

Beijing’s assault on US agricultural exports is blatantly designed to get the Trump Administration’s attention. China is the second-largest market for U.S. agricultural products, accounting for more than $19.6 billion worth goods in 2017. Further, this is the region of the US which heavily supported candidate Trump at the polls and helped deliver him the presidency. So, sowing some fiscal discomfort to the farmers and ranchers that rely on exports to China for a large slice of their livelihood is well founded.

The entire tit-for-tat or tariff-for-tariff exchange is nominally tied to the allegation that China has been dumping steel and aluminum products into the U.S. In most cases, trade disputes are referred to the WTO (World Trade Organization) to which both the US and China are signatories. But since the dispute was placed under section 232 of the U.S. Trade Expansion Act of 1962, the Trump Administration has taken the view the Chinese steel and aluminum imports “threaten to impair the national security of the United States” according to an April 4th letter sent to China’s ambassador to the U.S., Zhang Xiangchen.

While it is difficult to see how Chinese steel imports at 2.15% by weight or 3.35% by dollar value (2017 figures) are impairing the national security of the U.S. The real reason for tariffs (and thus China’s response) is much simpler.

From the onset, President Trump’s singular economic aim has been to find ways to reduce the U.S. trade deficit and China with a hefty $375 billion (2017) trade surplus is the main target.

China’s Trump Card

Early on in the dispute, China sent a warning shot across the Trump Administration’s bow. Since 2014 sorghum exports to China soared. The grain used for animal feed was also used in making Chinese liquor. China now accounts for 90% of U.S. sorghum exports.

On February 4th China announced it was launching an “antidumping” investigation on U.S. sorghum exports. Almost immediately all new sales of sorghum to China stopped. On April 17th, China announced it had concluded the investigation and determined U.S. sorghum was indeed unfairly subsidized. With that ruling in hand, China imposed a 179% duty on U.S. sorghum at entry. The suddenness of China’s announcement reportedly caught twenty ships at sea loaded with U.S. sorghum. The ships carrying 1.2 million tons valued at $216 million immediately began scrambling to find new destinations to avoid the 178.6% tariff.

Around 62% (2017) amounting to 1.4 billion bushels of U.S. soybeans are exported to China. At roughly $14 billion, it is the largest U.S. export crop. From the other perspective, China imports around $34 billion worth of soybeans annually or about 60% of the world trade in soybeans. So in May, when China cancelled 62,690 mt [Bloomberg] in retaliation for the Trump Administration’s tariff, the commodity market shuddered.

For decades U.S. agricultural interests like the ASA (American Soybean Associations) have worked to open China to U.S. soybean imports – the ASA says in their background report in opposition to the Administration’s tariffs, “China is perhaps our most impressive success story.” And as the numbers suggest, they have been very successful.

Whether China’s tactics have gotten the attention of the Trump Administration is hard to say – negotiations are reportedly still far apart. Nonetheless China’s move has garnered the attention of U.S. farmers. ASA (American Soybean Associations) President John Heisdorffer said, “ASA has consistently raised our significant concern since the prospect for tariffs was raised. Now this is no longer a hypothetical, and a 25 percent tariff on U.S. soybeans into China will have a devastating effect on every soybean farmer in America. Adding, “We believe strongly that soy can help reduce our trade deficit by increasing competitiveness.”

Still, like all trade wars – or in this case, skirmishes – there are rarely winners, China is going to have a difficult time replacing U.S. soy bean imports. Ramping up new production and shipments from other sources will be difficult, especially matching U.S. soybean prices. Brazil is the obvious choice, followed by Argentina and the development of China’s own domestic soybean crops. The latter comes at a cost – substituting one crop for another is often an expensive proposition.

Of the alternatives, Brazil, the world’s largest exporter (the U.S. is number 2), is the only viable alternative source and is unlikely in the short run to be able to fill the void.

From the U.S. perspective, diversifying exports is one solution, albeit a difficult one. U.S. Grains Council President and CEO Tom Sleight wrote in a statement, “In the near term, we will continue our work to diversify the markets to which our products are exported, focused on sales that can support prices this crop year. Based on our recent experience, we are well aware this work will be an uphill battle because our reputation as a reliable supplier has come into question.”

The question is not whether the U.S. can supply the crops but whether there will be a market for the goods given salted soil conditions of U.S. trade relations.

Europe is the logical market for U.S. soybeans but there is a trade war brewing with the EU. The next logical trade partner is Mexico, but with the current state of the re-negotiation of NAFTA treaty, Mexico may well look to other suppliers.

On the horizon, with TPP-11 going into effect, countries like Australia will have an advantage over the U.S. – competition not only in the China market but throughout Southeast Asia. It is worth noting that one of the diverted China shipments ended up in Vietnam, a market destination that might not be competitive for the U.S. in the future.

Future

Although China’s cut purchases of U.S. soybeans (and other agricultural products) and substituted more imports from Argentina and Brazil, it isn’t necessarily catastrophic to U.S. farmers…for the moment. Generally, this is the period of time, when China buys from South America.

The USDA is still bullish for exports to China for the 2018/19 crop year, despite China’s own agricultural ministry forecasting lower imports. Both might be right.

If the trade dispute isn’t resolved, it is difficult to see how U.S. soybean exports or that matter most agricultural exports will rise. On the other hand, if the U.S. and China resolve their trade differences, the USDA forecast of a 6.2% increase in soybean exports to China could be right.