Page 1: Renewables Power New Business

Page 2: Balancing Fossil Fuels and Renewables

Balancing Fossil Fuels and Renewables

The country known for its quaint windmills is in the forefront of modern-day wind energy, with onshore wind being increasingly augmented and supplanted by wind generated on the North Sea. The Netherlands predicts it could produce 11.5GW of offshore wind energy by 2030. That equals about 37% of current electricity needs. Some 10% of the North Sea is scheduled to be an energy production area by this time.

This focus on wind and other renewable energy sources is indicative of efforts by Dutch ports to better incorporate sustainability into their operating mindset, and their marketing focus. “We would like to facilitate and catalyze as much as possible the move to a more sustainable world,” said Eenhuizen.

This experience is useful for ports in other countries grappling with similar issues.

It’s a hard balancing act. The Dutch populace increasingly demands a greener future and the ports are eager to demonstrate they can embrace environmentally progressive policies.

But that’s not an easy task, necessarily. Ports represent one of the Netherlands’ most important economic centers. They aren’t just transportation and logistics hubs. Heavy industrial zones lie within their borders.

For many Dutch, the ports continue to embody a greenhouse-gas emitting, fossil-fuel dependence, with their high-profile depots, crackers, tanks and pipelines. Two of ten power plants on the Rotterdam port premises are still coal-fired.

The Port of Rotterdam is highly dependent on petroleum-related business. It forms the foundation of the port’s industrial core. Supertankers unload crude at Rotterdam terminals. Five refineries operate within the port complex, including the Shell refinery, which is Europe’s largest. Add to that another nine tank terminals for oil products and pipelines connecting the crude to other industrial sites in the south of the Netherlands and to refineries in Germany and Belgium, plus 28 chemical manufacturers.

Port authority officials recognize this dilemma. “Oil and oil products is quite a big commodity,” said Steven Jan van Hengel, senior business manager, shippers and forwarders, at the Port of Rotterdam. However, he added, “that is changing and evolving now, with the Paris Climate Agreement and the energy transition we’re in. So, that’s a big, big challenge,” He addressed a group of journalists hosted by Netherlands Foreign Investment Agency.

“Rotterdam is very much a fossil-oriented port. That’s where we’ve seen our biggest growth in the last decades,” added Eenhuizen. “The port area itself accounts for a large share of the emissions in the Netherlands.”

The port’s response, Eenhuizen said, isn’t to immediately jettison existing business, but to welcome new business “It’s an ‘and, and’ strategy, in which we slowly move from one industry toward the other, not in a single day, not in a single year, but something that will happen over time.”

This will eventually result in a new business model, Eenhuizen said, that is sustainable and centered on renewables.

He cited the port’s power plants, which are connected to the high-voltage power grid through onsite transformers. New transformers linked to the grid will also be installed for use by the wind farms.

The Port of Amsterdam also relies on fossil fuel as a revenue source. It’s the world’s largest gasoline port. Aviation fuel is piped from the port to Schiphol Airport, 15 miles away.

Rather than turn its back on these refineries and gasoline transporters, the port should work with them to develop and promote a greener future, Brenninkmeijer believes. She cited as one example the development of bio-kerosene as a synthetic jet fuel.

“They have the knowledge, the expertise and the people equipped for the new future fuels,” said Brenninkmeijer.

The ports see a role for themselves as well in moving ships and shipping toward environmental responsibility. One question the industry is being asked: “How do we get the current maritime industry changed to what’s more sustainable?” explained Brenninkmeijer. “The ports can accelerate this transition.”

As ports turn more of their attention to offshore wind and other renewable energy-related business, it would seem to result in overheated competition. Not so, said Brenninkmeijer. “We can’t do this alone, so we have to work with all the other ports to meet the challenges,” she said. “The complexities are so big, the investments needed nationally are so big that you cannot build alone.”

Paying for this transformation isn’t easy, either. “One of the big dilemmas is about changing the infrastructure for the future,” said Brenninkmeijer. “We have to invest [as a port] in this infrastructure. but we have to do this with our partners.”

In wind alone, this reflects increased demand for marshaling facilities as more and more developers seek to harness the North Sea energy. Part of this involves ancillary operations such as cables production and storage. Part of this involves production and assembly of the components themselves.

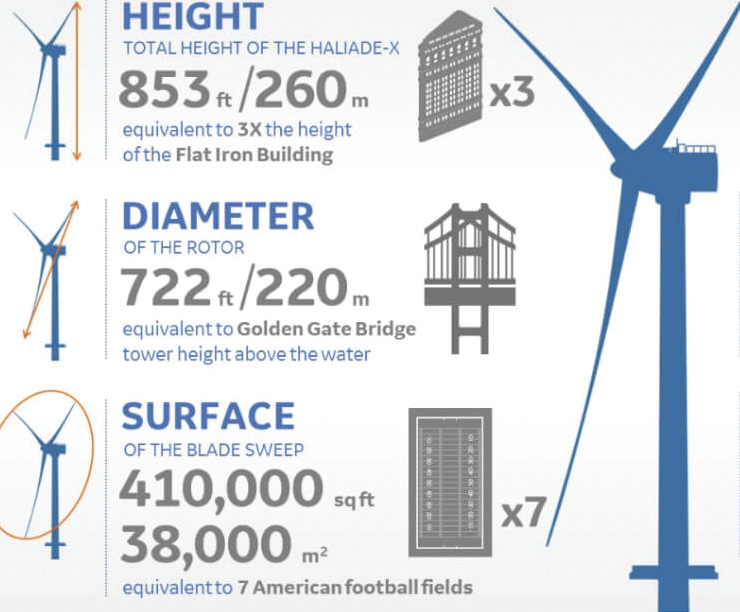

Space is one big constraint. Marshaling yards must be large enough to accommodate massive wind turbine components. And because these components are so large, it’s becoming increasingly necessary to construct or assemble onsite. The port of Amsterdam, for example, has reserved 35 hectares for wind-related production companies.

Wind farm operators demand precise timetables for construction; the purpose-built vessels necessary are hugely expensive. So, to insure exclusivity, even more space is necessary.

Then, there’s the maintenance of these farms when operating. And, there’s the decommissioning and dismantling of oil rigs and demobilizing of older generation wind turbines, which will be shipped elsewhere in the world.

“The whole system is going to change. The production of energy will be close, in the North Sea,” said Brenninkmeijer. However, she added, it will take some time, with planners looking at 2030 to 2050 for this transformation.

“We shouldn’t look at this as one player who profits from this,” Brenninkmeijer concluded. “In the end, we will all profit from this.” The Netherlands will profit from this.