Page 1: The TMI

Page 2: The MPP Sandwich

The MPP Sandwich

The MPP is different from most other types of vessels. In the main, containerships compete with containerships, tankers with tankers and bulk carriers with bulk carriers. Shipping is a seagoing bazaar largely dictated by supply and demand – freight versus space. But the MPP situation is different. “We say that the MPVs are in a ‘sandwich position’ as they are not only impacted by ‘supply & demand’ but by other market influences,” Prehm said. For example, if container ship rates are low, the carrier could move to poach project or breakbulk freight from the MPPs. The same holds true for ro-ro carriers, which are often actively looking for freight to supplement their primary freight of vehicles with back haul cargos. And ro-ro carriers with their enormous open space below decks are a natural competitor to MPVs for oversized cargo. And it happens with much the same caveat as containerships – in times when rates are low and the cargo fits the routing schedule. Even other larger dry bulk carriers can come into play in the MPP market. There are cases when a bulk carrier doesn’t get the 30,000 tons it was expecting, it might parcel out the loads and pilfer freight from the smaller MPP market.

While one would expect that the larger mega-containerships running upwards to over 20,000 TEUs with fewer port calls and often in VSA (vessel sharing agreements) that enable a number of ocean carriers to divvy up slots and cargo priorities within one ship, to abscond from dipping into the breakbulk market, not so according to Prehm. He cited two recent occasions, one when Airbus parts were moved via a 10,000 TEU boxship from the manufacturing plant in Germany to assembly in China and another more dramatic case, where wind turbine blades on flatbed racks were loaded on a 20,000 TEU CMA CGM ship. As Prehm points out CMA CGM has a large division dedicated to breakbulk and they are not alone.

MPP Market

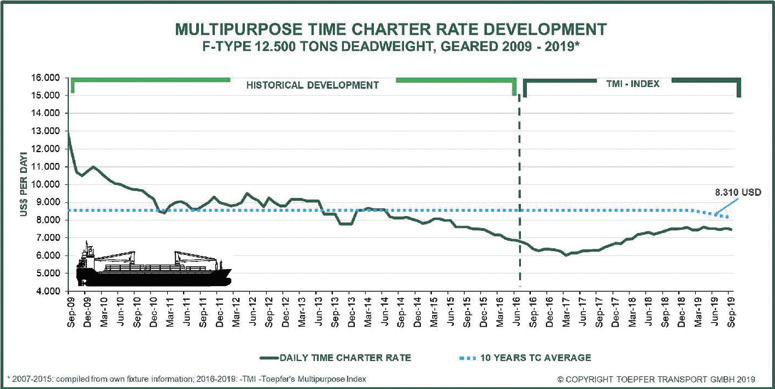

As a MPP neophyte looking at the TMI (see graph on page 20) for the last twelve months [Oct.-to-Oct] what stands out is how little stands out. The timecharter index moves in a very narrow band or as Toepfer in their latest quarterly MPP shipping report noted the paradigm, “The TMI is oscillating around USD 7,500 and we anticipate that this will continue to be the case for some time.”

Such steadiness is unusual for niche shipping markets as the vacillations in supply and demand often rock rates like ships in a tempest. But in the case of the MPP fleet, this is the calm following the storm – “ten bad years” as Prehm puts it.

Analysts cite a number of interrelated reasons for the relative steadiness in MPP sector. Right now, newbuilding amount to a miniscule 2% of the existing fleet and the fleet’s average age is a modest 13-years old with a normal life span of 25 years. As Prehm pointed out, some of the 10-12 year old vessels built in China were built to lower standards and likely will have shorter lifespans which could factor into a future scenario of demand lifting rates.

While many analysts are expecting freight volumes to improve as macro-economic indicators are forecasted to trend up for many of the industrial sectors serviced by MPVs, there are a number of caveats. For example, the impact of the implementation of IMO 2020 (see Peter Buxbaum on page 7) could dramatically alter the forecast for the MPP in 2020 and beyond. One of the outstanding questions is whether the post-IMO fuel surcharges will stick with the BCOs (beneficial cargo owners)? If MPV owners can’t recover fuel costs, will it result in a trimming of assets and potentially shipowners exiting the business? Another question related to IMO 2020 is what impact it will have on MPV fleet renewal? Relative to newbuildings, shipowners have some difficult choices in equipment and propulsion (engines). For example, what would the service impacts be if an owner opted for an LNG powered MPP? MPPs often call at smaller ports frequently located in developing nations – what’s the likelihood of such ports having LNG bunkering facilities?

There is also a great uncertainty in how the next generation of MPPs are financed. The German ship financing system which provided the underpinning to the last industry growth spurt (and subsequent overtonnaging) is all but gone. And institutional financing favors big ticket items at a $100 million a pop while MPPs are around $20 million a ship. And traditional banks are risk adverse to financing newbuildings.

So far, as the 2% orderbook implies, most MPP shipowners have adopted a “wait and see” approach to newbuildings, holding the fleet size in check.

But there are shortcomings to a stable market. While stability can lead to rate increases, it also means the fleet isn’t modernizing and is less efficient in fuel and other operational aspects. Some BCOs – particularly in the wind industry - are already worried about the ships carrying their freight and won’t take a ship older than 12.5 years because of the high insurance premiums. After all, any setback on a major project because of a delay in delivery whether it is in the O&G [oil & gas] or wind power sectors could cost multiple years and many millions of dollars.

Still there are lots of reasons to be sanguine. The O&G business keyed to rising energy prices is putting projects back online that have been on the shelf for seven years or more - offshore oil and LNG projects are showing life. And there are still the mainstays like paper, lumber, steel and steel products to keep the MPPs afloat.

Prehm says in the short term he’s forecasting “the market improving steadily but slowly.” And when asked about the future for MPPs, he’s “carefully optimistic.” For a class of ships sandwiched in business by other vessel types, even a modest uptick would be welcomed.

_-_28de80_-_58820516bd428ab3fd376933932d068c43db9a4a_lqip.jpg)